A Guide to Disagreeing Well

A Guest Post from Nick Argall: Sound advice for honest brokers

Greetings.

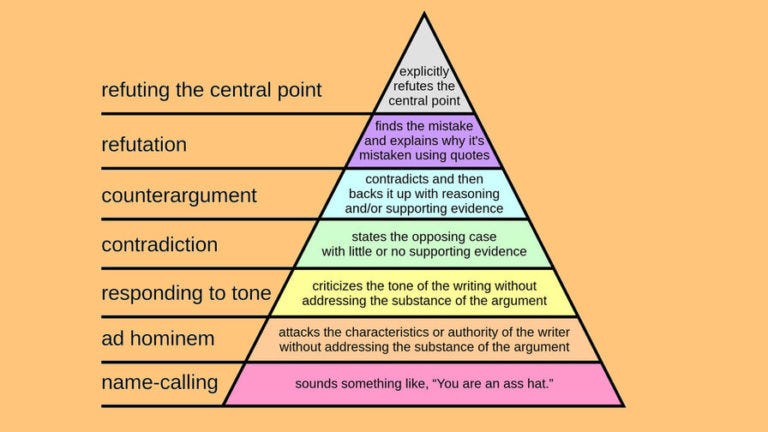

This is a guest post that Nick Argall, an organizational consultant whose post on how to disagree well has appealed to me for years. I asked Nick if I could post this short essay as a guest post, and he agreed. The image below is taken from an article I often share with students during the unit on the Art of Argument in the Reading and Writing for Academic Success course I teach. It is from the 2018 BigThink article How to disagree well: 7 of the best and worst ways to argue. There are a few small items that I do not agree with entirely. But, in the end, Nick’s message will resonate with most well-wishing people, as it has resonated with me.

A guide to disagreeing Well

*Originally published on Medium.com by Nick Argall

I tend not to shy away from controversial topics, and I enjoy having intelligent disagreements with people. If I’ve started a disagreement with you, that’s an indicator that I think you’re intelligent, and that you might say something to me in response that might give me a greater perspective on the world. Alternatively, it means that I like you, and I think that you’re making a mistake, and that there’s a non-zero chance that you might listen to what I have to say.

Either way, please take it as a compliment that we’re having a disagreement — I will endeavour (and sometimes fail) to regard your investment in the conversation as a compliment. It’s entirely possible that you share my attitudes towards disagreeing with people. Alternatively, you think I might be fun to play with.

Disagreements with me that go sour often have a pattern to them: A person (either of us) will put forward a course of action. The other person disagrees. People try to persuade me that the goal they are trying to achieve is worthwhile; I agree with them. They then try to persuade me that the problem they are trying to resolve is real; I agree with them. They then restate their original position, and I continue to disagree with them.

On a good day, we realize that the argument isn’t about what it seemed to be about, we identify the actual disagreement, and progress is made. On a bad day, I am accused of being ‘the enemy’ (take your pick from ‘SJW’, ‘Misogynist’, ‘Terror Apologist’ or ‘Racist’) or of simply being insane. This essay is written in the hopes of increasing the number of good days.

I’m sure that there’s a very good thing that you want. I probably agree that it’s a very good thing.

Things that I also want include (but are not limited to):

Diversity of all kinds within and between societies

Safety against terrorist attacks, and other violent crimes

Responsible conduct from all members of society

Respect towards people’s right to make choices about their own lives

Protection against people’s tendencies to make poor choices

I’m sure that there’s a problem that you care about. I probably agree that it’s a very real problem.

Problems that I recognize include:

Systemic biases in systems that undermine how they should work

The fact that white men (like me) tend to get more money, more promotions, and other good things

The fact that white men (like me) tend to be poorly educated when it comes to managing emotions, handling stress, and other important things

There are religious texts that tell people to do bad things, and there are people who pay attention to those texts

Society tends to condone various forms of violence

There is not enough money to do everything at once

People often hurt themselves, the people they love, and the things they love

That last one, for me, is the one that I care about most. I’ve hurt myself, I’ve hurt people that I love, and I’ve hurt things that I love. I can’t fix what I’ve done, but I’m constantly looking for ways to address that problem (for myself, and for others).

Nick Argall is an organization engineer, structuring activities to help businesses achieve their goals. nargall@gmail.com

My disagreement probably relates to a course of action

If I’ve started a disagreement with you, then there’s a good chance that I’ve interpreted your statements as saying one or more of the following:

We should solve this problem through violence

We should solve this problem through coercion

We should solve this problem by overturning the system / via revolutionary change

We should solve this problem by taking actions that might negatively impact innocent people

We should blame victims more

We should punish perpetrators more

We should not talk to our enemies

We should ‘just do better’ (also ‘just think’, ‘just try harder’… pretty much anything starting with ‘just’ and finishing with a verb)

If you’ve started a disagreement with me, then there’s a good chance that I’ve been trying to say one or more of the following:

Violence is a last resort

Coercion breeds resistance and resentment

Revolutionary change breeds counter-revolution. When it succeeds, it tends to replace one flawed system with another flawed system, at terrible cost

Harming innocents decreases legitimacy

Blaming victims isn’t helpful, because it denies the agency of the perpetrator

Blaming perpetrators isn’t helpful, because it doesn’t change the behaviour of the perpetrator

Talking to your enemies is extremely useful, if you can do so safely

If ‘just doing better’ was going to work, it would have worked already

If one of those ‘candidate disagreements’ matches the conversation we are having, then please recognize that I am rather inflexible on those points. If you think I might have misunderstood the situation (and matched it to one of my bullet points), then please let me know.

Not actually a question

Sometimes, people (including me) ask a question when they want to be reassured that they already have the answer. If you suspect that this is happening, then please let me know & we can shut things down.

No permission to be a teacher

Sometimes, people (including me) set out to teach people things. This can cause problems when the would-be student doesn’t want to learn this particular thing from this particular teacher. If you suspect that this is happening, then please let me know & we can shut things down.

Shutting down gracefully

I think it’s important to recognize that sometimes, smart people who want to reach an agreement (even an agreement to disagree) are unable to do so. When I want to exit gracefully, I try to signal that intention without continuing to present my argument. When you want to exit gracefully, I find it easier to understand if that signal isn’t mixed with other signals.

How I feel about all this

I’m increasingly aware of the fact that people invest hours and significant amounts of mental energy into trying to persuade me of things, and they end up frustrated and unhappy. I feel worse about that than my own frustration and unhappiness (not that I particularly like feeling frustrated and unhappy), mainly because I know what I’m in for when people argue with me — others might not.