Carrying a Message Further • Part 3: The Ground Experience in a World of Ideological Capture

Staying grounded when the temptation to conform to narratives is overwhelming

This is the third chapter of “Carrying a Message Further”, Part III of All We Are: Dispatches from the Ground Experience. This collection of writings explores the problem of ideological rigidity in social theories, the concept of "lived experience" (including my own), and the argument for using empowerment as a basis for education.

From the late summer of 2021, through the fall and beginning winter and on through the Spring and summer of 2022, I continually—and agonizingly—held out hope that I would have an opportunity to complete the writing of two additional chapters of “Carrying a Message Further”, the second major section of the “All We Are” series—a collection of writings that explores the cultural shifts and civil strife of the current era from a contemplative perspective.

But it wasn’t to be.

The two chapters I have been working on are tentatively titled “The Rightful King” and “The Sacred Victim”. Both of these chapters further explore the themes around the “primacy of identity”, which were introduced in Dr. Erec S. Smith’s book “A Critique of Antiracism in Rhetoric and Composition”. But, as I noted in the July 18th post in which I honored my late sister, it has been a full year since I have been able to publish any new content.

The reason for this gap year is that I was called upon by unique circumstances to put my ideals into practice in the real life professional context of teaching at the Benjamin Franklin Cummings Institute of Technology (BFCIT), a small technical college in Boston, Massachusetts that the Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Civil Rights of the U.S. Department of the Interior has designated as a Minority Serving Institution (MSI). And, as our college serves 74 percent students of color, including 37% Black and 28% Latin(x) students, many of the ideas I’ve been exploring in the “Carrying a Message Further” chapters have real world implications on the reality of the ground in my professional work, which is why I chose to reallocate most of my energies from the “All We Are” writing project to the concrete world of teaching and learning in an institution that required those energies.

In light of all this, I’ve decided to insert two additional unplanned chapters into “Carrying a Message Further” that explore the larger context in which I teach as well as my collaboration with colleagues in the development of publicly documented projects at BFCIT to help provide readers a concrete context for the themes I’ve been covering in these writings.

After all, the ideas, values, and concerns that these writings explore can only matter in the end when we consider how these ideas, values and concerns affect reality on the ground.

The Ground Experience

Originally, I had not planned on including my professional work in this series of essays, but given the level of output that was required of me in my professional life over the past year, and, given the direct relationship between that output and the themes I have been exploring in these writings, it now makes every sense in the world to include some of the realities on the ground from my professional life as an educator in a college that nearly closed. The choice to include these experiences also makes sense when I consider that one of the overarching themes of the “All We Are” series is the importance of reconnecting our hearts, minds, spirits, and bodies with the ontological ground, the actual empirical unconditioned reality that objectively exists beneath the realm of thought—that is, to reconnect with the ground experience.

I have already covered the question of empiricism versus the postmodernist principles of deconstructionism and standpoint epistemology in Part II of this series, “Beyond Cynicism”, so readers who might question my assertion that empirical (objective) reality exists on some level will hopefully understand that I have given a great deal of thought to this question. Though I may lean in the direction of positing that an objective reality exists and can be known, I also acknowledge that at least to some extent, our subjective conditioning can “color” our perceptions of this (proposed) reality, which means that we have to take into account the many parts of ourselves that might inform or distort our perceptions, and thus, our beliefs and actions.

In the language of Critical Social Justice (CSJ) theories, we can be said to have a “subject-position” on the social and cultural map of our shared reality. This means that, according to CSJ, our sociocultural identities contribute substantially to our ability to accurately perceive what is actually in front of us. Thus, our gender, gender identity, ethnicity, racial identity, age group, religion, personality type, neurological patterns, sexual orientation, body type and size, and many other factors that make us who we “are'' renders our subjective experience of reality (including how we experience other sentient beings in that reality) almost entirely unreliable in determining what reality actually is.

Though I have a good deal of respect for the idea that our ability to perceive and understand reality can be compromised by our personal identities, histories, and socio-cultural makeup, I part ways with followers of CSJ in my taking the unambiguous position that such conditioning can be overcome and that reality can, in fact, be known. This position is unfalsifiable in that I cannot prove it. But the idea that reality can be known is no more an unverifiable assertion than many of the claims made by those who adhere to the deconstructionist practices of CSJ (e.g. racism is everywhere at all times and the only question worth asking is not whether racism has occurred in a situation, but how).

The possibility that we can experience reality outside of our subjective conditioning is a position that runs through all of the writings in the All We Are series. In fact, the very name of the series implies both:

a statement that implicitly challenges CSJ adherents’ belief that extreme subjectivity is the alpha and omega of all existence, and;

a proposal implied in the rhetorical question: is this really all we are?

For me, the question of “is this all we are?” is closer to the truth than the proposed answer of “this is all we are”.

This brings me to the reason for naming this Substack page and my other personal website “Ground Experience”. I’ve been researching and drafting Part I of the All We Are series around the theme of differences and overlaps between the ground experience and the doctrine of lived experience, and I think now is as good a time as any to briefly explain what I mean when I say that the “ground experience” differs greatly from what some call “lived experience”.

Ground experience points to reality underneath ideology. Lived experience points to both the unfiltered information and natural insights that can emerge from the experience of actual events (which, of course, is legitimate) and the idea that a person’s personal experiences somehow dictate that person’s ability to, understand, perceive, experience, and have insights into those experiences.

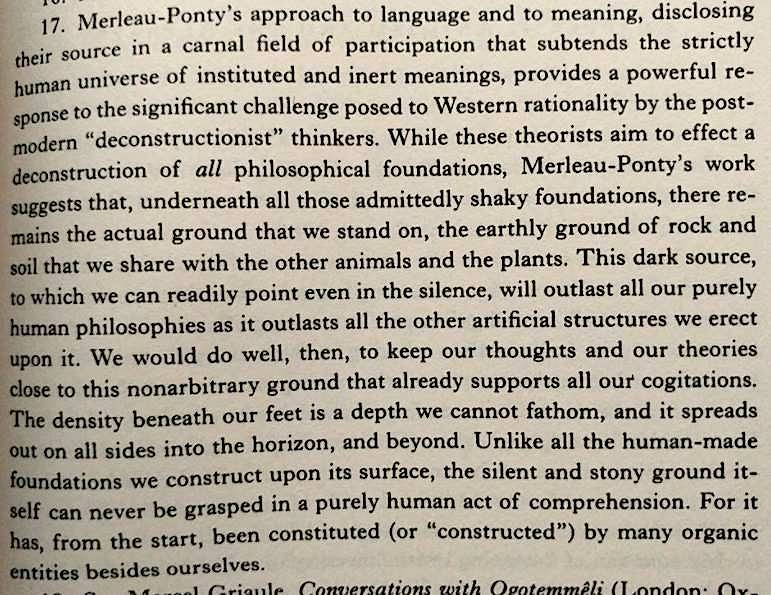

Some time ago, I found an image on social media and recognized immediately that the words in this image perfectly captured what I’m calling the ground experience. The writer who is referred to in the text of this image is Maurice Merleau-Ponty, a French philosopher who studied and wrote about existentialism and phenomenology and championed the importance of staying connected to the real world outside the realm of abstraction and “cogitation”—the world of thoughts, beliefs, attitudes, egoic speediness, runaway imagination, political commitments, excessive theorizing, and raw emotionizing. Before I published this post, I could not locate the source of the text in this image, so I chose to insert the image below and offer a few brief comments about it, hoping that sometime down the road I would find out who the author is. Fortunately, after I published this piece (now edited, of course) a reader reached out to me and informed me that the passage below comes from The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World By David Abra.

This image above immediately struck me the moment I saw it.

Its message is clear. Abstract theories and worldviews, including tradition-oriented belief systems, deconstructionist theories, religious doctrines—all frameworks that structure our perception of ourselves, others, and reality itself—ultimately rest on a shaky foundation. And what is a foundation if it’s shaky?

As long as we are allowing our perceptions and perspectives to move away from what the passage above calls “the actual ground that we stand on, the earthly ground of rock and soil that we share with the other animals and plants'', we are not only lost and confused, but opening ourselves up to the potential for dropping more darkness and even cruelty into the world. According to this passage, we would be wise to regain our natural allegiance to the “non-arbitrary ground” of empirical experience, for this experience is reliable, providing, as it always has, an unconditioned foundation for all of our thoughts, beliefs, habits, desires, fears, and all other “artificial structures” that we choose to “erect upon it.” It’s also the empirical reality experienced by other people—we perceive as separate and distinct from ourselves. Put another way, the ground experience is the beingness—the ontological reality—that lies beneath all of those same things that have been “constructed by many organic entities besides ourselves”.

So, it’s a fancy way of saying, let’s stay connected to what is real and empirically verifiable beyond our thoughts, fears, suspicions, and ideological positions.

Admittedly, this is hard to do, especially when we are saturated by information relentlessly coming at us in a 24-hour news cycle; and inundated by media interpretations of events and people that are biased towards specific political ends and tailored towards our desires to achieve the goals of the ideologies we identify with. It’s becoming increasingly more difficult to discern what is real from what is not real.

And, for people teaching in a highly politicized educational milieu on any scale (from society to an individual school, department, or classroom), the project of discerning what’s true and real from what is not true and real becomes even more difficult.

It also becomes potentially perilous for us in the inter-related areas of economics and reputation if we cannot successfully navigate our way. Thus, we are required to find a way to walk between the raindrops. A middle way.

The Middle Path

Teaching in a Minority Serving Institution (MSI) in a major East Coast city in the United States presents a challenge for those of us who have chosen the middle path—the path of what Greg Thomas has called the “Radical Moderate”, a path in which we must continually challenge ourselves not to fall prey to ideological possession, interpretive absolutism, and interpersonal cruelty in the name of our ideals. A path in which we must also be willing to challenge our own preconceptions and ideological commitments so that we can practice open-hearted immediacy, and learn to meet other people on their own terms. This way, we stand the best chance to find pathways to co-existing peacefully while also maintaining our commitment to both truth and justice. It is the path of epistemic humility, which is a very difficult path to travel in environments that have been captured by specific ideologies—especially what Robert J. Lifton called totalist ideologies that allow no room for fresh perceptions, original thinking, or innovative solutions that lie outside those already prescribed and imposed upon us by the totalist ideology that has become ascendant in our environment.

There are more of us who strive to walk this path than we might be led to believe.

Just today, I came across a similar perspective advanced by Africa Brooke, whom I made reference to in the previous chapter about The Problem of Bullying in Social Justice Activism. On Erec Smith’s “Free Black Thought” Twitter page, the following image was shared, along with a link to Brooke’s Instagram page, where she posts a two-hour conversation with Salomé Sibonex, a young writer and visual artist and philosopher, whose written work covers many topics, including the psychology of the self, and many dimensions of identity in both individuals and society.

Africa Brooke’s words here speak to me and many others who wish to avoid the extreme path of ideological totalism, even in the service of the highest ideals. Though it’s not easy, many people are finding their way towards the more dynamic and hopeful path of the “radical moderate”, especially after seeing the increasing social, cultural, and political polarization of the world over the past decade as many politically charged people have confused authenticity with the act of doubling down on beliefs without evidence and the accompanying patterns of finding a one-dimensional enemy to hate and the ego-comforting idea that the hate is justified by an intelligent-sounding ideological framework.

As Brooke points out, we can in fact be in “the middle” without being milquetoast, fence-sitting, or non-committal to our values and principles, as long as we are willing to speak openly and candidly about what we are seeing or perceiving without resorting to social violence and rigid thinking. We can even be fiercely committed to a cause while practicing kindness and the willingness to question our own ideological conditioning and cognitive biases. Ultimately such a path requires a sense of embodiment, where we stay connected with the physical sensations of our body, maintain awareness of our emotional reactivity, and commit to slowing down our thought process long enough to really “take in” the world around us, including the people in that world.

What does any of this have to do with the effectiveness of the work of a college professor at a minority serving institution? And what does this have to do with the important project of working towards both depolarization and social justice? Everything. Without the academic and ethical freedom to deliberate, openly inquire, or present alternative solutions that lie outside orthodox ideology, we condemn students of color to low-grade educational environments, and we banish those charged with the duty to educate those students towards a kind of professional purgatory characterized by powerlessness, fear, and the depression and frustration of no longer having the ability—or even the permission—to really make a difference in people’s lives.

Political Cultism in Educational Institutions

In the end, what is called for in any educational institution that seeks to accomplish its mission, is to actively defend against the lure of becoming a political cult—a rigid ideological community that no longer seeks the quest for truth, but that seeks to create an insular environment where not only is the pursuit of knowledge nearly vanquished, but a reduction of intelligence and the increase of interpersonal abuse and intergroup suspicion becomes the norm.

In my own professional context in which I work with students of color in a major city where many of its institutions, non-profits, political movements, schools and colleges are directly influenced by Critical Social Justice theories and practice, the rapid growth of political cultism presents a unique challenge. Within the next few years, for example, the Boston Public Schools system will be formally adopting an ethnic studies curriculum—one that is highly controversial and that many believe could potentially worsen racial tensions in our communities. As the curriculum is built upon the foundational belief drawn from Critical Race Theory that American society (and all of its systems) is entirely structured by “The Pillars of White Supremacy” and that students from different ethnic groups are assigned the roles of “oppressed” or “oppressor” based solely on their group membership, most reasonable people who have not been captured by this ideology have some reason for concern.

I have already explored the problem of group identity essentialism in Chapter 2 of “Beyond Cynicism”. I mention it here because, as the reader may recall, group identity essentialism posits that we can know the inner lives of individuals simply because they belong to a certain identity group. One example of how far group identity essentialism can go once it has become foundational to a theory or curriculum is a research article that Newsweek reported on in June of 2021, in which “whiteness” was described by Dr. Donald Moss as a “malignant, parasitic-like condition”. The fact that this article was published in the Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association should be of concern to those who worry that the “helping professions” have begun to be influenced by an ideological framework that actively engages in bigotry under the guise of academic theory and a commitment to extreme and narrow conceptions of social justice.

Just a year earlier in February, 2020, Dr. Moss delivered a lecture for the Center for Modern Psychoanalytic Studies that was advertised as a discussion about the ways in which “Parasitic Whiteness renders its hosts’ appetites as voracious, insatiable, and perverse” with “deformed appetites” that “particularly target non-white people.” In recognition of how hard it might be for the reader to believe that such rhetoric exists and has entered the helping professions, I’ll let the advertisement of the talk speak for itself.

It helps to keep in in mind that these are not isolated incidents in which one influential thought leader in the broad field of psychology slipped up and temporarily went down the rabbit hole of “Critical Theory Gone Wild”.

According to the Newsweek article mentioned above:

“Moss has previously lectured on the subject of whiteness before On Having Whiteness was published in the bi-monthly, peer-reviewed Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association on May 27. In 2019, he delivered his theory describing whiteness as a parasitic condition as a plenary address for the South African Psychoanalytical Association, and he also lectured on it at the New York Psychoanalytic Society and Institute and at the Center for Modern Psychoanalytic Studies in New York.”

It is no wonder that there has been some recent pushback against what can, once again, be reasonably called political cultism. We see this pushback among thoughtful, educated, and compassionate professionals in both the “Critical Therapy Antidote” movement that aims to bring the therapy and therapy-adjacent professions back into the business of helping people, rather than increasing inter-group conflict and the potential for physical and social violence. And we see this pushback in the Constructive Ethnic Studies movement , which aims to bring awareness to racial injustice, unfair systems that have held many communities of color back from the success that should rightfully be theirs, and the teaching of history that is candid, committed to even the most unflattering depictions of historical atrocities, intergenerational trauma, and unjust systems, but that does so without automatically assigning behavioral traits, intrinsic desires, and the level of morality to entire demographic groups.

We can also see the pushback from academics like Dr. Lyell Asher, whose series “Why Are Colleges Becoming Cults” expertly lays out the historical timeline of the institutional capture by extreme versions of Critical Social Justice Theory and the long-term implications.

It should be easy to see how such “teachings” can indoctrinate young people into either hating themselves for being “parasitic oppressors” or into being suspicious of people who belong to the disfavored identity groups that they have been trained to see as naturally wired to want to do harm to them. Such suspicion can lead to anger and even violence, and at the very least, we can all but count on the invocation of violence and cruelty from less morally developed people who would opportunistically use such teachings for their own nefarious purposes.

The tendency of opportunists to use us-against-them ideologies for their own self-gain and for the sheer pleasure of hurting and abusing others was described succinctly by Aldoux Huxley in his 1921 work of fiction, Crome Yellow:

“The surest way to work up a crusade in favor of some good cause is to promise people they will have a chance of maltreating someone. To be able to destroy with good conscience, to be able to behave badly and call your bad behavior 'righteous indignation' — this is the height of psychological luxury, the most delicious of moral treats.”

When considering the proliferation of the institutional promise to mistreat people for their disfavored demographic identities and the ascent of political cultism in education and other helping professions, many academics and therapists have chosen to leave their professions altogether, seeking greener pastures where complex theories with shallow and abusive moralities do not yet rein supreme.

The Para-Academic Movement

The dissatisfaction with the rising political cultism in academia and the difficulty of the job market, a new movement has recently come into existence that celebrates and encourages people to become “post-academics”. One blog called Escaping the Ivory Tower was put together by a Ph.D former tenured professor of rhetoric and composition who calls herself “Julie” and explores in a simple way just what it means to be a post-academic and why many are choosing to leave the profession. Though she does not mention the challenges around ideological extremism in her choice to leave the teaching profession, she mentions the many other grueling elements of this profession that cause many academics to eventually leave—low pay, lack of support from administrators, and the burnout that comes from being available practically 24/7 to both students and colleagues.

When you put all of these things together and add the growing phenomenon of hostile workplace environments brought on by group identity essentialism and active bigotry backed up by legitimate-sounding academic “theories”, it’s no wonder that we are seeing a mass exodus.

But, for those of us who are becoming ever more dedicated to independence of thought, the need to protect the freedom to follow our conscience and to study and write about the world without the confining shrink-wrap constraints of ideology— who also want to maintain a connection with educational institutions and to continue contributing scholarship and knowledge-production—a new community-based movement has arisen in recent years called the para-academic movement. A useful resource for developing para-academic skills and networks can be found in The Para-Academic Handbook (Book): A Toolkit for Making-Learning-Creating-Acting, which was edited by Alex Wardrop and D-M Withers. In the description of the book, the editors have this to say about why para-academics have chosen their new life path:

“Frustrated by the lack of opportunities to research, create learning experiences or make a basic living within the university on our own terms, para-academics don't seek out alternative careers in the face of an evaporated future; we just continue to do what we've always done: write, research, learn, think and facilitate that process for others. As the para-academic community grows, there is a real need to build supportive networks, share knowledge, ideas and strategies that can allow these types of interventions to become sustainable and flourish. There is a very real need to create spaces of solace, action and creativity.”

As I am currently considering moving into the field of elder care (after nearly a decade in learning how to provide care to the elderly, especially those with dementia), I am encouraged by movements like the para-academic movement that advocate for us to continue to contribute our knowledge, creativity, expertise, questions, and independent research to the field of education while building networks of support that lie outside the confines of institutional authority and ideological capture.

For now, I continue to be inspired to continue teaching in spite of the encroachment of groupthink and ideological totalism into virtually all realms of the education field. And I continue to be inspired to pursue the radically moderate middle path that springs from the commitment to staying connected with the ground experience so that whatever I produce in the world can be generative and generous.

More importantly, I continue to be inspired and deeply honored to have the opportunity to contribute to an institution that serves student communities who have not yet been adequately invested in. An institution that, so far, has maintained its dedication to the development of knowledge and expertise, while simultaneously reaching for the very heights of social justice for those have been far too long on the sidelines of society.