Carrying a Message Further • Part 5: The Primacy of Identity

Reclaiming anti-oppression from the sacred victim narrative and ideological hardness

This is the fifth chapter of “Carrying a Message Further,” section III of All We Are: Dispatches from the Ground Experience. This collection of writings explores the problem of ideological rigidity in social theories, the concept of "lived experience" (including my own), and the argument for using empowerment as a basis for education.

In this chapter of “Carrying a Message Further”, I will introduce ideas around the experience and perception of victimization and its connection to rhetoric and self-expression with the use of insights from the book A Critique of Antiracism in Rhetoric and Composition, which was written by Dr. Erec S. Smith, Associate Professor of Rhetoric at York College and the co-founder of Free Black Thought (see FBT manifesto here).

It has been two years since I began the “All We Are” project, a series of essays that explores the intricacies, promises, and perils of the cultural and political polarization we have been experiencing in the West for decades, and especially during the period between roughly 2014 and 2023. It may strike the reader as odd to see the word promises in that sentence. The major promise that I am referring to is that many are now coming to recognize the problem of polarization, which means we stand a better chance than we did just a few years ago to understand the mechanics behind that polarization and to hopefully find ways to move through and beyond it.

And the important work on depolarization could not be more timely.

Just this week, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a decision to abolish affirmative action in student college admissions. The next day, Dr. Aisha Francis, the President of the Benjamin Franklin Cummings Institute of Technology (where I teach) posted a message to the college community of the college’s website declaring her allegiance to organizations and movements that oppose this ruling and affirming the college’s dedication to advancing the life and career prospects of students from historically marginalized communities.

As a Minority Serving Institution (MSI) with one of the largest populations of minority students in the United States, a ruling like this one is likely to cause a lot of reflection in our community at large and bring into high relief the issues and controversies around the balance between merit-based academic achievement and the need to correct, on the institutional level, for imbalances of opportunity that have marginalized students of color for a long time.

And that reflection is happening all around us.

In the Atlantic article, “‘Race Neutral’ Is the New ‘Separate but Equal’”, Uma Mazyck Jayakumar and Ibram X. Kendi stated their opposition to the ruling plainly. “The result of the Court’s decision: a normality of racial inequity. Again.”

They go on to argue:

“Admissions metrics both historically and currently value qualities that say more about access to inherited resources and wealth—computers and counselors, coaches and tutors, college preparatory courses and test prep—than they do about students’ potential. Affirmative action attempts to compensate not just for these metrics that give preferential treatment to white students, but also for the legacy of racism in society.”

Though I am ambivalent about the Supreme Court’s decision and have strong disagreements with the way equity is practiced in many institutions, workplaces, schools, and colleges, I have to agree with Jayakumar and Kendi about the differentials in educational opportunity that exists between different demographic groups, schools, and districts. I’ve seen this up close as a public school teacher. One example (admittedly anecdotal) that comes to mind is that when I taught journalism to all the 6th, 7th, and 8th graders in a large K-8 school in Boston, the Advanced Work Class (AWC) I taught two years in a row comprised one hundred percent white students, most of whom came from wealthy families with big houses, after-school programs, vacations, nice clothes, and the latest digital gadgets. This was simply not the case with most of my other students (who were mostly Black and hispanic).

The authors of this article also cite a study about the unfair advantages that many white students have historically had in the college admissions process, contending that white students admitted to Harvard often have their own form of affirmative action. Some call these types of admissions legacy admissions, which in the article includes “recruited athletes, legacy students, the children of faculty and staff… [and] “relatives of donors—compared with only 16 percent of Black, Latino, and Asian American students.” They also conclude that 75% of white students would not have been admitted to Harvard if they had not belonged to one of these four privileged categories. Though I’m not sure about the accuracy of these numbers, I think the general trend of the privilege behind legacy admissions is fairly identified.

It’s unusual for me to find agreement with Kendi’s analysis on a social issue related to race. I’ve been critical of Ibram X. Kendi’s Manichean outlook that insists that we are either one hundred per cent for his own program for racial justice (what he calls “antiracist” and I call “ideological antiracist”) or that we are against all antiracism (which means, in his worldview that we are racist). For several years now I have come to believe that his contributions to discussions around race (alongside Robin D’Angelo) have largely poisoned the conversation around race and racism, forcing people into highly polarized tribes characterized by what I call “ideological hardness”, which is unfortunate because as an historian, Kendi X has much to offer.

The problem of ideological hardness is one of the greatest problems I see in the West, and by all measures it appears to be getting worse. In a 2018 study on depolarization called “Hidden Tribes of America”, the largest group of Americans who shared a political outlook were found to comprise what the study’s authors called “the exhausted majority”, those who do not feel at home in the ideologically hardened camps that are all too often reluctant to acknowledge even the partial truths of the camps on the other side of a social or political issue.

As a member of the exhausted majority and as a college professor who teaches developmental and advanced reading, writing, and communications courses at a Minority Serving Institution, I, like many others, find myself caught between the proverbial rock and a hard place, especially when it comes to racial issues, as it's increasingly hard to find allies who see what I see in its fullness and nuances. As George Yancey carefully explores in his book Beyond Racial Division: A Unifying Alternative to Colorblindness and Antiracism, I am unable to be persuaded to adopt the extremely ideological versions of antiracism (which New York Times writer and Columbia University linguist professor John McWhorter cleverly calls “KenDiAngeloism”) or the lukewarm, whitewashed version of pure color-blindness that does not make room for the reality that large communities of black people have traditionally been set aside or actively pushed to the margins and continue to experience the negative impact of historically oppressive policies. I explore this topic in some detail in the first part of “Carrying a Message Further” called “Why Educators Must Read Erec Smith”, but I’ll briefly summarize below.

It’s okay to acknowledge that sometimes the struggle is real.

I know firsthand the specific hurdles faced by many students of color who live in the Greater Boston region where I teach, and I am well-versed in the language that is often used to describe these hurdles during advocacy work, grant-writing projects, and policy discussions.

Phrases such as food insecurity, transportation insecurity, intergenerational trauma, lack of access to tutors and coaches, and lack of representation in the texts students read during their schooling years are phrases that I not only agree with but have actively used in my own behind-the-scenes advocacy work in educational spaces. I am also aware that in some classes, schools, and districts, there is a lack of recognition that many students (often of color) don’t speak Standard American English in the home and that many were not born into a reading culture where their parents read to them on a regular basis during their early years. The disparity in the time that parents are available for adapting their children to reading is partly related to the disparity between different demographic groups in the advantages of one-parent homes and two-parent homes.

A 2015 Pew Research Survey provides the following statistics related to two-parent homes: 72% of white, 82% of Asian, 55% of Hispanic, and 31% of Black families have two-parent homes. This means that in some homes (particularly Black homes) a higher burden is placed on a single parent to provide the time to read to a child, which some research has shown to have a significant impact on student achievement in reading and writing. There are larger discussions to be had for how to address this disparity and similar disparities. I mention it here because I have to agree with the authors of the Atlantic article that there are some structural hurdles early on in the lives of students from different groups that affirmative action policies were designed to create a correction for.

There is also a tremendous burden placed on teachers in both K-12 and higher education environments to provide learning experiences that account for not only disparities but the large number of variants that influence students’ capacities to have successful schooling lives. This is something that my college recognizes, and it’s something I’ve been called upon to play a role in addressing. As part of my work with the Faculty Development Committee, I collaborated with the Director of Learning, Sally Heckel to bring in Universal Design for Learning (UDL), which is a teaching methodology designed to accommodate multiple learning styles, linguistic subcultures, learning disabilities, neurodiversity, English Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) and other factors that all students uniquely bring to the classroom at all educational levels. As part of the college’s re-accreditation process, I was also asked to collaborate with the Director of Curriculum, Mozhgan Hosseinpour, to re-design annual program reviews for all departments and programs, and I was given the opportunity to write out the section on UDL and inclusion, which aims for an integrative and less ideological approach to assessing educational outcomes in programs and departments.

In the next few chapters chapters, I hope to cover some of the aspects of UDL that dovetail with diversity and inclusion, especially those specifically related to language and communication (and Smith’s critique of how ideological antiracist “praxis” often compromises the whole effort), so I’ll set this aside for now.

Overcoming struggle is real, too

I want to say something clearly and unambiguously about my firm belief that we also have to include self-empowerment, merit-based achievement, a love for learning and knowledge, and a rigorous approach to intellectual and moral development in the education of young people from Kindergarten through post-graduate studies.

Even while we may choose to continue our efforts to even the playing field (in a reasonable non-ideology-based way, which I call responsible equity), we also need to inculcate into young people the understanding that they must resist the magnetic pull towards considering themselves as “lesser” than others, regardless of where they come from and regardless of the obstacles and hardships they face—including the obstacles and hardships that are universal to all human life, such as death, braving the cold, being bored, and physical pain. We also have to refrain from the fashionable practice of teaching students to be resentful and to feel entitled to being genuflected to, catered to, or unfairly advantaged over others who are deemed more privileged to settle scores for historic injustices or correct for the suffering they have experienced in their own life journeys.

In other writings, I’ve alluded to my own upbringing as a member of the “poor white trash” subculture that involved drugs, prostitution, violence, abuse, reliance on government assistance, fraud, and criminality. I know what it’s like to grow up in a network of despair, and I have lost people from my past (including a family member to a police shooting) who, partly due to circumstances they were born in, led lives of survival choices that eventually contributed to their untimely and sometimes violent deaths.

So, I get it.

But, I, too, come from that world. And I believe part of the reason why I’m where I am today is that I was fortunate enough to have interventions from relatives, adults, teachers, and mentors who believed in me and who provided me with other models for a way out of the life I came from. My stepmother (long since divorced from my father), is one of the top mentors of my life, and, in fact, I would go as far as to say that she is one of the great saviors in my young life. She told me back in 2008 that she always felt it was important for her to provide me with “cognitive dissonance” to keep me from gravitating towards the alluring world of crime and despair that was around me during my first twelve years. She set an example early on that I wanted to follow, and even after she moved away when I was 7 years old, I continued to want to make her proud well into my teenage years. To put it simply, I did the “good boy” thing. I went to school, got good grades, stayed out of trouble, and eventually navigated my way into new, better and more promising worlds over the years.

So, I was greatly helped by the influential people in my life who taught me to practice strength, self-discipline, and perseverance and to put my best foot forward in all circumstances. It was their efforts in empowering me that kept me going, and they did not allow me to indulge an identity of being a victim or to feel sorry for myself.

To be clear, I am not comparing my own circumstances to the “Black experience”, nor do I mean to draw exact parallels with the sufferings of any other demographic group or to minimize other peoples’ difficult experiences. I also don’t mean to universalize my own perspective as though it automatically applies to the lived experiences, wisdom, and understandings of others. But, I am saying that our society has to develop a wiser and more mature understanding of victimization, trauma, identity, healing, and social progress than the current offerings of anti-oppression narratives that are being advanced in the media, educational spaces, and in the rhetoric of influential thinkers, writers, leaders, and political figures.

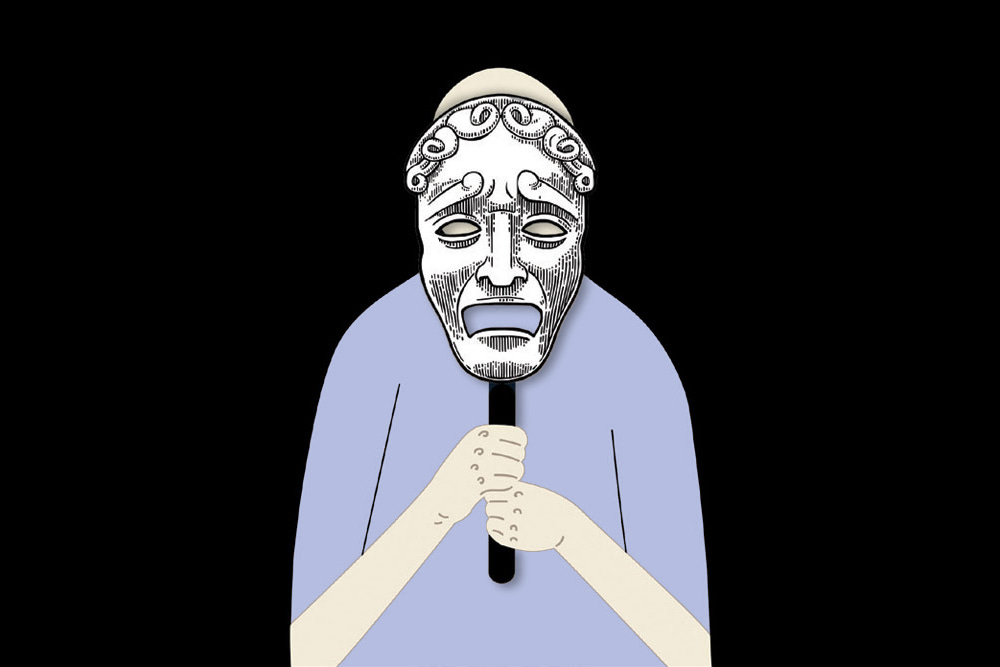

The sacred victim narrative and the rhetoric of identity

Erec Smith declares in the beginning of the book that the goal of writing the book was “to rescue anti-racism from the sacred victim narrative”, and he makes a distinction between that narrative and the narrative of the “rightful king” (which I will be exploring in a later chapter):

“Unlike the rightful king narrative, in which its protagonists want to re-acquire the power they have apparently lost, thus doing harm to the Other while uplifting themselves, the protagonists of the sacred victim narrative are doing harm to themselves by taking refuge in a prefigurative politics instead of working to actually instill beneficial change.”

When Smith speaks about the sacred victim taking “refuge” in preconfigurative politics, he is referring to a form of anti-hierarchical community-building that seeks to “pre”-model the ideals of the egalitarian world the smaller community is actively working to create. The idea is that people who have taken on a victim identity and have chosen to band together—for example, forming a housing cooperative, or creating an insular environment of a classroom in a school or college where people who identify with similar identities communicate only to each other and choose not to venture out of their bubble ideologically or sometimes even socially.

From the beginning and throughout the book, Smith draws a clear connection between the identity of the sacred victim and the lack of access to the genuine ability to persuade others for the simple reason that the speaker, writer, or orator, is coming from a solipsistic self-enclosed sense of identity with a weakened ability to have a fuller sense of the audience, timing, and social environment in which the sacred victim is communicating (which is called “kairos” in classical rhetoric). In other words, the effectiveness of a speaker or writer’s rhetoric and communication (and connection with the outside world) is largely connected to the degree to which the communicator is invested (or overly invested) in an identity.

Although the book covers many themes, one of the most central themes can be summed up in the critique Smith offers early in his book that we disempower ourselves and lose our effectiveness in the world as long as “the primacy of self-expression” [takes] over other fundamental aspects of rhetoric, especially kairos and audience consideration.” One of the most fundamental aspects of rhetoric,” Smith exhorts us to understand, “is its suasion; it conveys information in ways that audiences can understand, or it conveys information that will sway an audience toward some kind of action.”

Most would, of course, consider this simple description to be common sense—so much so that it almost doesn’t even need to be said. But Smith insists that the simple wisdom around effective communication is often lost in the communicator who emphasizes identity and self-expression rather than communicating useful knowledge and understanding.

“Rhetoric in the primacy of identity is less about the audience and much more about the rhetor. The rhetorical triangle of speaker, subject matter, and audience gives way to a circle with the rhetor in the center, with the subject matter and audience rotating around it. “

He goes on to describe rhetoric variously as the “practical instruction in how to make an argument and persuade others more effectively”; “strategies that people use in shaping discourse for particular purposes”; and other definitions including protest rhetoric, performative rhetoric, and others. But, the key statement on page 5 is this one:

“One can strategize to shape discourse in a way that overemphasizes a rhetor and de-emphasizes an audience.”

As I hope to adequately describe in the current chapter and the chapters that follow, excessive emphasis on the sacredness of being a victim and deep immersion in the sense of ourselves as rigid, reified individual and/or collective identities can have some very dark consequences for individuals, groups, and even whole societies as our very sense of reality and our ability to communicate with one another and make sense of the world becomes lost, confused, chaotic, and in the most severe circumstances, dangerous and violent.

“Carrying a Message Further” and Antagonistic Cooperation

Smith has been quite busy over the past two years, since I began “riffing” on Critique of Antiracism in Rhetoric and Composition (more on “riffing” below!). He has participated in a fairly large number of podcasts and public talks, as well as conferences (including the Counterweight Conference for Liberal Approaches to Diversity and Inclusion which I presented at and helped recruit presenters for); and he has written many articles in multiple platforms, including his Free Black Thought page, and by the looks of it, I don’t seem him slowing down his output anytime soon.

Yet, I still regard this book to be central to my own contemplations around social and political polarization and especially my contemplation around teaching and learning and the examination of the variety of viewpoints around how best to serve students of color, and more specifically Black students of color. In a sense the way I’m approaching my writing about the book in, “Carrying a Message Further”, much like “Beyond Cynicism”, can be likened to an improvisational jazz session in that the instrument I am playing (a series of essays in this case) is “riffing” off the original themes of other instrumentalists who started off the music session with the books they’ve written, and allowing myself to improvise my way down a kaleidoscopic path that hopefully retains the essence of the original themes (the ground experience) of the books while allowing the creativity of my own variations to express itself.

In some passages and chapters, I am likely to engage in what some jazz theorists call “antagonistic cooperation”, which can be likened to sharpening the knife while softening the dough. Integral Theorist, writer, and jazz musician Greg Thomas (as well as several other jazz musicians) has written often about antagonistic cooperation and considers the process of playing improvisational jazz music as a metaphor for creative engagement with the world in its many domains—including the social and political domains (see Thomas’ powerful riff on the idea of “racelessness” in his excellent essay “Racelessness Now”, in response to the writings of Glen Loury and Clifton Roscoe). In his essay, “Primary Principles of Jazz”, which he wrote for his Jazz Leadership Project website Tune Into Leadership, Thomas describes an important aspect of antagonistic cooperation in the following way:

“In life and work, syncopation is being prepared for the shifts and changes that arise. Swing is a coordinated response to life, where there’s a ground rhythm and groove to depend upon so when we venture out to experiment and improvise, that bass and drum will be right there, like a carpet of support. The antagonistic part of the principle directly above is tied to syncopation, the cooperation to swing ...Together, the practices point to a robust resilience that prepares you to even be anti-fragile, where you can thrive through uncertainty or chaos.”

This passage speaks to me both as a musician and as a writer. The two controversial books I am choosing to improvise upon in the All We Are Series can be considered the bass guitar and drums—the grounding experience of the rhythm section— that I can rely on as a foundation as I “venture out to experiment and improvise.” That’s the cooperation part. The antagonistic part will come in later chapters when I critique some of the ideas put forward from the writings I’ve been “riffing” on and experimenting with in my choice to bring in other frameworks including metamodernism (in the arts and larger culture, the influence of Black metamodernism, in particular, and some aspects of the arch-disciplinarity movement—all of which seek to combine knowledge from multiple disciplines into comprehensive “meta-theories” that aim to build an understanding of the world that transcends and includes social, political, individual, and economic systems. I will also aim to bring in occasional references to spiritual disciplines, including Engaged Buddhism which has some insights that I believe play an indirect but important role in Smith’s book and some of his critiques of Critical Social Justice Theory (CSJ). The antagonistic aspect of bringing in other paradigms is that I would be occasionally situating the intelligent and well-thought-out critiques that the writers have worked hard to express in their writings inside frames that purport to both include and transcend their critiques. Some people call this bracketing, and it’s fair to say that this can sometimes be experienced as quite antagonistic.

Ultimately, I believe that all writers and advocates who are sincere in their efforts towards sense-making and truth-discovery are engaged in the organic unfoldment of collective intelligence. Whether we call it antagonistic cooperation or antagonistic collaboration, it’s the “co-discovery” aspect that often leads to advances of knowledge.

Okay, but what’s up with the word “riffing”?

An interesting note about the word “riff”. Ironically it can have opposite meanings. In jazz and other types of music, the “riff” is the repeated chord progression and/or drum beat that continues for an indefinite period of time that allows the soloist (singer, saxophone, guitar, etc.) to experiment. But, according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the noun “riff” is also described as “ distinct variation” (or a take) on an original riff, and the verb “to riff” means “to perform, deliver, or make use of a riff”.

So, I’m making use of the original writings of the authors featured in the All We Are series and riffing on them, not so much as an indulgent thought experiment, but as a contemplative exercise to go deeper into truth and to hopefully find my way towards a more complete sense of truth, even as reality itself (and its “truths”) continues to evolve.

W.E.B. Dubois: Origin of the Phrase “Carrying a Message Further”

The phrase “Carrying a Message Further” itself is something I've been riffing on. This phrase comes from a quote that Smith shares from the Black scholar, Harvard Ph.D professor, and civil rights activist W.E.B. Dubois, who in 1909 was one of the founding members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Although I will go into more detail about what I consider the deeper aspects of what this phrase means in a chapter dedicated to Smith’s conceptions of pragmatism and empowerment in the teaching of reading, writing, rhetoric, and composition, the short version of the context behind this phrase goes like this:

Dubois was a self-described “angry” Black student when he first went to Harvard University in 1888. During his freshman semester he wrote a fiery essay about his experiences of being a Black man in the post-reconstruction South and the evils of political leaders who at the time engaged in outright racist hostility against Black people, including the audacity of using the worst racial slurs in public writings. Dubois was so proud of what he wrote and just knew that he had found his voice, and he expected to receive a high grade on the essay. However, his professor of English composition was not impressed and gave him an “E”, which at the time was the equivalent of the modern day “F”.

In Dubois’ own words:

“My long and blazing effort came back marked “E” —not passed!”

But in the end, Dubois was grateful. From that point on, he learned that in order to be heard, he would have to learn how to carry his message further, far beyond the bounds of his understandable rage and even his sense of identity. How else would he be able to reach those who needed to hear his message most? How much further could he expect his message to be carried if he doubled down on a fixed sense of identity and intense preoccupation with his isolation from others, however justified that sense of identity must have felt?

The Central Problem of Ideological Antiracism: The Primacy of Identity

Smith establishes early on in the book (and in other recent writings) that the central problem with ideological antiracism and the way it shows up in many Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) programs, activist communities, policy-making endeavors, and education programs is the primacy of identity. But he makes clear in the third page of the first chapter that he has no quarrel with identity politics nor with the term identity politics itself. The phrase originally referred to the action of people coming together as a group to advocate for themselves and to demand more rights or more resources, which is a time-honored tradition for people all over the world who have had to rise up against tyranny in all its forms.

Smith makes it clear that he supports identity politics and that we should, too. And, after sharing a little about the history of the term (which was coined by Black feminist scholar Barbara Smith in 1974 for the Combahee River Collective), he then makes the following distinction between identity politics and what has chosen to call a “primacy of identity”.

“To distinguish from the [Combahee River] Collective’s take on identity politics, I have named the current academic manifestation a ‘primacy of identity’. As the name indicates, the recognition and expression of identity takes precedence over other considerations, and is almost immune to critique.”

In a way, the primacy of identity can be seen as counterintuitive to the adversarial cooperation of “improvisational jazz”, which involves open-minded engagement and creativity as well as open-hearted inter-relatedness between individuals and groups. One could argue that improvisational jazz is about loosening up our habit of freezing an identity for ourselves. To play jazz well (and perhaps to live well among others in a pluralist world), one has to learn to step out of oneself and to acknowledge others, and to engage with others on their own terms (as well as on our own terms) in a way that harmonizes, complements, and sometimes challenges. We cannot effectively challenge the perspectives of others if we have not learned to see deeply and accurately into those perspectives and into our own reactions to them.

And we can’t even come close to that type of playfulness and good faith engagement if we are intent on freezing and refreezing our identities. In this light, we can reasonably say that the primacy of identity in an individual or group’s relationship to the world is a profoundly debilitating condition.

In a nearly ancient New Republic article (1994!) called “Against Identity”, writer Leon Wieseltier wrote that the ability to transcend our identities long enough to deeply regard the reality of others on their own terms is characterized by “selflessness.” He put it this way:

“Identity will always look suspiciously on selflessness. But selflessness does not mean that you do not know yourself. It means that you have been drawn out of yourself. It is the self-denial of the strong.”

Given the recent cultural phenomenon of hyper-primacy of identity, especially among young people, this insight seems to hold up. Our ability to be drawn out of ourselves—to let go of our narcissistic impulse to focus only on our own identities and needs—if only temporarily—offers an opportunity to relate to the other “selves” in our immediate surroundings and world at large. As I’ve written elsewhere, the strength of practicing what Wieseltier calls selflessness (or at least a good faith reaching out to others) lies in a fearless commitment to developing a more porous, flexible identity (while maintaining integrity in terms of our values).

But in the current era, which is dominated by reductionistic group identity theories that freeze individual and collective identities and that cause separation and sometimes active hostility between entire demographics (some of them are exceptionally wacky), I acknowledge that this is hard to do. In fact, identity is one of the hardest things to unravel. Even more so in an era in which we are considered somehow unenlightened, misguided, and even bad for choosing not to over-identify with the socio-cultural identities that have been applied to us by ideologically motivated theorists. Being open to the experiences of others is especially difficult if an individual’s identity has become the primary orientation in that individual’s sensemaking of the world, which seems to be the chief aim of group identity theorists.

There is, of course, a time and place for identity being primary for us. In psychologist Erik Erickson’s theoretical framework of human development, adolescence (around ages 12-25) is described as involving the pendulous swing between identity and confusion as young people (emerging adults) search for who they are and for the proper way to relate to society as individuals with separate, distinct identities. This is a natural process. But it’s hard to deny that over the past decade this stage of human development has been extended well into peoples’ mid twenties and even early thirties—especially for those whose college education has taught them to intensely focus on their separate individual and group membership identities and to feel entitled to being seen by the world how they’ve chosen to see themselves. It’s almost a willful reinforcement of the ego principle, the daring-do of a 17 year old boy at the wheel, full of booze and hypomanic impulses, buzzing on down the highway, pushing 100.

So in the present era, the pendulous swing between identity stability and identity confusion that was previously confined to the developmental stage of adolescence has come to take up a much more central role in today’s society as people just coming out of extended adolescence join the workforce and become more influential powerbrokers in workplaces across many professions, the political and social realms, and interpersonal relationships. Thus, identity (as a clear and unmistakable marker that separates us from others) has become a powerful driver for our culture with a rapidly driving force that we haven’t known before.

The Primacy of Identity as Disempowerment

In A Critique of Antiracism in Rhetoric and Composition this cultural force that Smith calls the primacy of identity is described as especially prevalent in students who have been trained to see themselves primarily as a member of a racialized group. In particular, he is critical of an approach to teaching students—and in particular, students of color—that reinforces a victimized identity, which he describes as a deficit model that introduces, reinforces and then prioritizes students’ self-conceptions as disempowered individuals rather than as people with the agency and capacity for actualizing their potential for being powerful and impactful in the world.

A year after the book came out (2020), Smith elaborated further on this idea in the Newsweek article “Redefining 'Harm' Infantilizes People of Color”, in which he declares:

“I, for one, refuse to be harmed so easily. I refuse to let people have so much control over my happiness and fulfillment. My anti-racism is about promoting empowerment. I cannot say the same for others.”

Throughout many of Smith’s writings, including this book and his articles and essays, he goes deeply into the distorted ways in which students who have been trained to see the world through the lens of victim disempowerment and systemic oppression tend to read situations, fellow people, and the written and spoken words of others. As a scholar and professor of rhetoric and composition, Smith’s main concern is how the primacy of group identity often clouds students’ ability to regard the empirical aspect of reality, facts over narrative and, most importantly, the ability to consider what he succinctly calls “audience consideration, and logos”. In other words—how identity gets in the way of communication and relationships with other people and the larger society.

On page xiv in the introduction, he writes:

Although I will discuss pedagogy to some degree, my main argument will be political and ideological. I argue that anti-racism initiatives and the narratives and ideologies that feed them result from a “primacy of identity” that, itself, results from a strong sense of disempowerment that leads to fallacious interpretations of texts, situations, and people; an infantilization of the field, its scholars, and its students; an overemphasis of subjectivity and self-expression over empirical and critical thought; an embrace of racial essentialism; and a general neglect of rhetoric itself, especially regarding context, audience, consideration and logos.”

However ambitious his attempt to cover all of these issues may appear to some readers during the reading of the introduction, my own careful and comprehensive reading of the book demonstrated at least to me that Smith succeeded in illuminating important truths that impact not only race relations, educational pedagogy, the art of rhetoric and communication, and society in general, but somehow integrates them in a coherent and digestible way—thus carrying the message to us all.

In the next few chapters, I will explore some of the deeper dimensions of the sacred victim identity from a more contemplative angle, zooming out to the larger reality of the inherently violent nature of the cosmos and sentient beings, and zooming in on the aspects of the victim identity that are related to individual and collective trauma, historical oppression, and the wide variety of views that exists among people from all walks of life regarding all these things.