The Wages of Disembodied Theory • Part 2

Challenging the Belief in a Pervasive Malevolent Force

*This is the second chapter of “The Wages of Disembodied Theory”, which is Part I of All We Are: Dispatches from the Ground Experience. This collection of writings explores the problem of ideological rigidity in social theories, the concept of "lived experience" (including my own), and the argument for using empowerment as a basis for education.

Introduction

In the spring of 2021, during the height of the racial justice protests, I encouraged a community I participated in as an advisor to take a more moderate approach to racial justice workshops. I attended several meetings with various people of influence in the community and presented my concerns using reasoning, research, and some of my writings on these issues, making sure to always present my questions, ideas, and concerns with clear tie-ins to the mission and goals of the community.

Fortunately, after candid discussions and through sincere, collaborative efforts, the community adopted a moderate approach to facilitating racial harmony, justice, and belonging among members of the community.

However, despite our eventual progress, I encountered a significant challenge during the early stage of my advocacy. One influential community member dismissed my proposal, highlighting what I believed could become a deeper issue within the community if not addressed. While the person expressed appreciation for what the person called my passion, it was also communicated that, in the end, I was just “a white male,” implying that what I had to say about the issues the community cared about, and what I hoped to bring forth in the proposals I was presenting, did not have value. Overall, I can say that I feel satisfied with the conversations we had in the community around difficult issues, and I am happy to report that the community was able to avert the meltdown atmosphere that had been characteristic of many communities during that time and in the years since.

But that statement reverberated with me deeply, not because I received it as a personal slight, but because it highlighted a broader pattern that I was already worried about. It underscored how easy it has now become to dismiss someone's contributions based on their identity and how easily this broader pattern of behavior can undermine the mission of other communities I participate in.

Group Identity Theories as Structural Disenfranchisement

To be dismissed so casually was disappointing. I had well-prepared and researched insights that matched my experience and the community's goals, and was convinced that if more people had a similar viewpoint as this influential committee member, it would be difficult to make real progress on any community endeavor. If the ability to bring something valuable to the table that could help a community’s mission is undermined because of a person’s supposed membership in an identity group that is disfavored in that community, then we have a clear situation in which that mission is compromised. To address this issue in any community, we need to ensure that contributions are evaluated based on their merit rather than the identity of the contributor. This approach helps communities stay true to their mission by modeling genuine, good faith cooperation.

If we allow group identity theories to dictate who can and who cannot speak about ideas that impact a community’s goals, we are engaging in a basic form of structural interference. And in those cases where communities have been set up to serve people who are disadvantaged in some way or those that have this service as a secondary goal, this interference becomes much more; it becomes a form of structural disenfranchisement. Using people’s identity against them to silence or delegitimize them ultimately disenfranchises the people the community was created to serve. This is why I found this casual dismissal so disappointing.

I believe the person who made this statement is a good person. I respect this person and feel confident that the person contributed much to the community’s well being and to its mission. And I also understand that the person’s words were in alignment with the current cultural zeitgeist, so, in the end, I have to make some allowance for those words and the spirit behind those words, coming as they did from a place of wanting to do good in the world (albeit by marginalizing someone). It’s also important to point out that I honestly do not believe that this person was out to hurt me or that the person wanted to intentionally undermine me for the sake of it. There was a complete absence of malice in the person who reflexively diminished all that I brought to the table due to my group identity membership.

But I have to contend, nonetheless, that I believe the reason for the person’s choice to devalue what I brought to the table was related to an ideological artifact that the person picked up from the current cultural zeitgeist—the claim by followers of Critical Social Justice (CSJ) that we can detect people's character, inner life, and abilities based on their membership of an identity group we have assigned them to.

The pattern of reducing the essence of people to their demographic identity markers is a problem that has confounded me for a good number of years now since my years in graduate school, where I first learned about group identity theories, and eventually came to write about in a piece called “The Problem of Group Identity Essentialism.”

Looking ahead in the next few installments, I will delve deeper into the implications of group identity theories through a contemplative lens and share insights from various writers and studies, alongside personal and professional anecdotes to propose frameworks that foster a more invitational approach—one that honors the humanity and collective wisdom of all members of the community.

Meta-Ideological Awareness and Depolarization

The Need for Meta-Ideological Awareness

In almost all of the Ground Experience writings up to now, I have shared and commented on the works of different authors with a variety of approaches to equality and social justice, with a general critique of a widely influential framework known as Critical Social Justice (CSJ). One of the overarching aims of these writings has been to explore the theories and sub-theories of CSJ with a commitment to practicing “meta-ideological awareness” in the effort to understand how these theories are constructed, the deeper most truthful aspects of these theories, and how and why they are carried out in our shared social reality.

Practical Applications

In a December 2023 Integral Life podcast, Ryan Nakade, a mediator and depolarization advocate based in the West Coast of the United States, systematically lays out the meta-ideological approach to transcending divisions and building relationships with perceived adversaries (and would-be allies!). In a graphic called “Insight Map” located on the podcast’s page, Nakade writes that “politics, economics, and social issues are some of the most epistemically corrupted fields, making it difficult to have mature, nuanced, and thoughtful discussions''.

Nakade notes here and in other sections of the page and podcast that learning to recognize how we are all corrupted epistemically (i.e. how we each have distorted ways of perceiving, observing, knowing, and interpreting) and learning to recognize the meta-patterns of how we ourselves are influenced by theories of reality can make it much easier for us to come to the table to collaborate with others in the important work of depolarization and thus “cohering social fields toward greater harmony”.1

Put in simpler terms, if we want to reduce polarization, we need to understand why we believe certain ideas are absolutely true. If you look at Nakade’s infographic below, you will hopefully find, as I do, that there are many variables to consider in the work of depolarization, including our willingness to become intimate with ideologies that we consider alien to us. While I am tempted to elaborate further in this moment on the intricacies of meta-ideological awareness and depolarization, I think the content in this infographic speaks well enough for itself.

Impact of Social Theories in New England and Beyond

After spending time exploring the maze of social theories over the past four years, I want to come back up to the surface and explore the ways in which these theories are carried out in real time in the New England and Greater Boston regions where I am employed as a college professor; and how some of these theories have come to shape the political and policy making process, the educational mission of institutions across all age groups, and the day-to-day relationships of everyday people in the New England region and beyond.

To keep the pace moving in this series of essays, I will approach this overview of the impact of ideology-based social theories by skipping rocks across a fairly vast pond, covering as much territory as possible in summary form to give the reader a sense of what it might be like for some people to be teaching in a region that has come to be governed by specific ideological beliefs that—when applied in a totalizing way—have a strong potential for being deeply divisive and harmful on every scale of human relationships from the water cooler, classrooms, and barrooms to the halls of Parliament, Congress, and international movements for social change.

An important recognition I want to offer at this juncture is that other regions in the United States, particularly the southern and midwestern regions, are governed by an entirely different set of beliefs and that there are conservative movements in those regions that seek to control narratives, conversations, and school curriculum in ways that are every bit as totalizing and authoritarian2 as some of the progressive movements in my own region. This recognition is an important component of maintaining my own commitment to meta-ideological awareness in that I have to occasionally step back and acknowledge that for very good reasons, many readers might not see what I see and may indeed find my own descriptions, concerns, and contemplative meanderings to be coming out of the patterns of hypervigilance and even hyperbole. Some who may one day read these essays may find themselves utterly perplexed that anyone of sound reason or mind could find anything problematic or worrying about the patterns I will be describing.

But, that’s okay. I think it’s at least going to be helpful if I can find a way to name the overarching patterns so that those who are experiencing them under a different set of beliefs might find solutions once they have recognized those patterns.

To make it easier to follow, I will present my observations and experiences of these patterns in five “landscapes”, each with its own unique flavor of what it’s like to experience the influence of a specific ideological framework on the ground.

The Ideological Landscape

The Political Landscape

The Educational Landscape

The Social Landscape

The Emerging Landscape

The reader may notice that I’ve chosen not to highlight media as a separate landscape. The reason for this choice is that media—which includes traditional newspapers and online journalism platforms, television, websites, video games, books, transcripts, signs, murals, sidewalk stripes, social media platforms, texting, chats, private messaging apps, and all other forms of communication and messaging—is arguably the most powerful and omni present landscape of them all3, appearing in all places at nearly all times, transmitting messages coming out of the other landscapes in a ceaseless stream.

As I head into the first landscape, what I’m calling the Ideological Landscape, I want to briefly highlight the influence of media by openly declaring my allegiance to a single practice that I believe helps me get a sense of where others are coming from in regards to issues that impact them and their loved ones—intentionally seeking out media and media platforms that do not immediately align with my own current beliefs and understandings.

By availing ourselves to left wing4 and right wing media—including media that some might consider far right and far left—and by diversifying my media ecosystem to include a variety of philosophies, including religious, secular, non-theistic, and atheistic philosophies, I feel that we have the benefit of having a more complete picture, which helps us to find joys and sufferings to empathize with and values that we can resonate with in people we might otherwise dismiss or misunderstand as coming from either a bad place or. In my own experience I have discovered countless times that—in my own ignorance—I had misunderstood some people to be coming from a less informed place than I was.

Turns out, in those moments, I was the less informed one. And sometimes the wrong one.

For a more in-depth look into how diversifying our media ecosystem intake can help us build a more complete understanding of the world around us and how other people tick, I highly recommend the essay, “We Don’t Make Propaganda! They do!” by the founders of the Consilience Project. This project—much like the work of social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, John Wood Jr’s Braver Angels depolarization movement, and Erec S. Smith’s Mutual Persuasion project (which I’m grateful to be a part of)—is close to my heart in terms of how to be active in the world of ideas, action, and social change in a way that upholds the standards of epistemic humility, curiosity, sincerity, and the willingness to question my own perspectives.

And that questioning of perspectives and the desire to discover what some are calling the “middle ground”, the liminal space, is something I look forward to further exploring in the final installment, which I’ve called the Emerging Landscape, in which I will share some recent developments that give a sense of hope and forward movement as more people and more communities are finding ways to move forward in their efforts not only towards depolarization but towards harmony and integration.

The Ideological Landscape: New England

Some Background about New England

I’ve chosen to focus on New England in this section in part because this is the place where I was born and the place where I have lived for five decades. It is also the place where I teach on the college level after spending nearly two decades teaching in public schools, which has provided me with many opportunities to see how the ideological landscape has developed through the years and the way schools and institutions of higher education have been impacted by that landscape.

But there is another more compelling reason.

The New England region has an almost unparalleled historical legacy, including the the events leading to the American Revolution and the birth of American liberty, the powerful influence of Boston advocates in the anti-slavery Abolitionist movement, the first public schools system, the first stirrings of the women’s suffrage movement, multiple arts and literature movements and technological innovations that came to impact the entire English-speaking world, and an ongoing culture of social, culture, and political progress, which makes the region and its largest city one of the most exciting and happiest places for people to live and for teachers to teach.

My Personal Connection to New England

I have always had a strong connection to this region and with four of its port cities as well as with its political and cultural history, both past and present.

Here is a quick run-down:

Born in the port city of Portland, Maine where my favorite poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow5 lived, I eventually migrated in my 20’s to the largest city in New England, the port city of Boston, Massachusetts, where I conducted historic tours in both Boston and Cambridge, stopping with passengers to view Longfellow’s pale yellow house on Brattle Street, the very same house where George Washington and his wife Martha stayed in 1775 during the period in which the General of the Continental Army was stationed on the Cambridge Common. At the time, I also performed re-enactments of the Boston Tea Party at a local museum, playing Paul Revere, the famous member of the Sons of Liberty, and Samuel Adams, who was famously described by Thomas Jefferson as “truly the man of the Revolution”

Some interesting family birthday connections here:

Samuel Adams was born on September 16th6, which is my own birthday. And as the second signer of the Declaration of Independence, he was present on July 18th, 1776 during the second public reading of the document in Boston. This date is my older sister’s birthday. Just two weeks before, this famous document of liberty was first read in public in Philadelphia on the Fourth of July, my younger sister’s birthday.

My Professional Connection to New England

And if those connections weren’t interesting enough, I wound up in later years as a full-time professor, teaching in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Benjamin Franklin Cummings Institute of Technology, a trade school that was established with funds left to the City of Boston by Founding Father Benjamin Franklin, who was born in Boston and worked as a printing apprentice until he moved to Philadelphia at age 12.

The connection with Benjamin Franklin is the most interesting to me because of the historic juncture at which we find ourselves in the English-speaking world, during which we are collectively navigating our way through the dialectic between the legacies of the Enlightenment and colonialism, and the postmodernist response to those legacies in educational institutions and the culture at large.

This juncture and its potential outcomes for the greater Boston and New England regions is something I explored in a 2023 essay called “Investing in Minority Institutions: Why I Chose to Invest in the Benjamin Cummings Institute of Technology.” As I wrote in that piece, I believe this is a great moment in the college’s history, as the institution is now led by the first woman of color, Dr. Aisha Francis, a highly recognized leader in the region and winner of multiple awards for her contributions to education, leadership, and the arts. Since 2020, Dr. Francis has led the college through many important stages, including the Covid-19 pandemic, the college’s successful reaccreditation process, and the fundraising, planning and development process of the college’s move to its new location in Nubian Square. And, I am happy to report that under her leadership and the leadership of her administrative team, the college’s finances are now in the black, which augurs well for the robust future that lays before us.

To say that this moment in the college’s history marks a partial fulfillment of Benjamin Franklin’s legacy and the legacies of Martin Luther King, Jr. (who graduated from Boston University with a Ph.D. in theology) is an understatement. With a population of more than 76 percent students of color, a quirky, diverse, and highly motivated staff and faculty, I truly believe that our college has an opportunity to model an approach to higher education and the diversification of the 21st century workforce and technological innovations for decades to come7.

This moment also marks a partial fulfillment of my work as a professor in the humanities and more specifically as a teacher of writing, reading, oral and professional communication, contemporary social issues, and the art of argument. As a longtime student of the depolarization movement, I have had the opportunity to be introduced to the depolarization work of Braver Angels, Mutual Persuasion, The Protopia Lab, the Institute of Liberal Values, Heterodox Academy, the Integral Theory and Metamodernist movements, the Human Dignity and Healthy Workplace movements, and a number of organizations and scholars who are working to promote unifying approaches to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI). It is to my great fortune that I am able to bring all of what I have been learning in depolarization work into the classroom, where I can introduce students to larger and more inclusive frameworks for living in the world as intelligent, powerful, civic-minded advocates for genuine progress.

The reason for my use of the phrase “partial fulfillment” is simple. The work of introducing students to fair-minded critical thinking, good faith communication techniques, honest rhetorical strategies, the humility to be open to other perspectives, and empathy-based universalist perspectives that also honor the unique experiences of identity groups and the unique personhood of individuals is never fully fulfilled. It is the kind of work that is ongoing—the kind of work that will need to go on for thousands of years and perhaps on through the end of civilization itself or the collapse of the sun.

And it is the kind of work that is very much needed in a highly polarized era marked by fears of a malevolent force hiding around every corner—a fear that has become almost foundational to worldviews across the political, social, and cultural spectrum leading to the wide-scale breakdown of social trust and hope.

New England is no stranger to this state of affairs.

Throughout the world, this region has become known not just for its political, cultural, and scientific contributions to humankind, but as the place where the infamous Salem Witchcraft Trials took place, a tragic tale in our history that will forever be the archetypal story that we refer to in times of pandemonium, fear, accusation, and epistemic confusion.

And that’s where we are now.

Historical Context: Salem Witchcraft Trials

From the early winter of 2017 through the fall of 2018, I rented a studio apartment just 300 feet away from the very spot where a radical religious ideology led to the horrific death of an innocent man. This death took place in Salem, Massachusetts, a small seaside town in the New England region of the United States, and was one of many atrocities that took place during the Salem Witchcraft trials of 1692-1693, in which over 200 people were accused of witchcraft after convulsions, screaming, and seemingly supernatural fits broke out among a group of young girls who came to blame their afflictions on the evil spirits (or specters) of the accused.

By the end of a terrifying period of accusations, pandemonium, and suspicion brought on by superstitious beliefs, greed for land, and status-seeking, nineteen of the accused (mostly women) were hanged, and one man, Giles Corey, was crushed to death with large stones, a method of torture called “pressing”, which was used to coerce a confession from accused people who refused to enter a plea to the court.

Though he had the opportunity to be spared an agonizing death, Corey refused to enter a plea to the court (guilty or not-guilty) because of a law at the time which required the sheriff of Salem Village to seize the property and belongings of all those who entered the plea (which they almost always claimed for themselves and their relatives). Corey wanted to ensure that his sons inherited his property upon his death, so instead of entering a plea after each large stone was placed upon the board on top of his chest, he simply cried “more weight!”.

Sadly, in horrific fashion, he eventually succumbed to the rib cage-crushing, blood ejecting, suffocating agony of the pressing procedure just months after his wife, Martha Corey, herself was hanged after being found guilty of witchcraft by the court.

Puritan Ideology and the Professional Ministerial Class

It is important to acknowledge that it was a set of disembodied theories propagated by the professional ministerial class—the premodern equivalent of today’s professional managerial class8—that led to an atmosphere of accusation and terror and the fifteen-month period of poverty, imprisonment, and death that came out of that atmosphere.

This class of people was made up of ordained Puritan ministers who established a theocracy on the eastern shores of North America beginning in the early 1600’s.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was established in 1630 when a group of a 700 colonists led by Reverend John Winthrop landed on the shores of the Shawmut peninsula (now Boston) to install a utopian society where a pure, uncorrupted, and non-papist form of Christianity, along with the accompanying beliefs about the Devil and witchcraft, could be practiced, free from interference from the Church of England, Parliament, or any other earthly authority. While the settlements were officially under the rule of the British Crown during this time and into the late 18th century, the governance of the proliferating townships during the early colonial period was localized under the rule of the Puritan ministers.

One of the most powerful and influential ministers during the time of the Salem Witchcraft Trials was Cotton Mather9, who was educated at Harvard College in Cambridge, Massachusetts and came to enjoy prominence on both sides of the Atlantic, publishing over 400 writings on a variety of subjects, both religious and secular, such as those related to ecclesiastical history, Biblical teachings, advice on relationships, analysis of poetry and writing styles, and even scientific writings, including numerous writings on smallpox inoculations10.

But Mather has become most infamously renowned over the centuries for his writings on witchcraft and for his influential role in the Salem Witchcraft Trials. While his role in the legal proceedings was not formalized, the influential theologian openly endorsed the trials and lent legitimacy and legal weight to some of the superstitious beliefs that were used as evidence in the trials through his personal letters to local Salem authorities and judges and through the publication of his widely circulated and reviled 1693 book, Wonders of the Invisible World, which provided a detailed defense of the proceedings and of the decisions made by the presiding judge, Lieutenant Governor William Stoughton.

Malevolent Forces: Spectral Evidence and Devilry

It’s important to note that while Mather didn’t support an end for the trials (indeed he actively cheered them on), he did advise those in charge of the legal proceedings that certain types of evidence should not be used as the sum total of the evidence that could lead to punishment by death. The evidence in question was called spectral evidence, and Mather insisted that while spectral evidence should be taken seriously as meriting the “presumption of guilt”, it was not provable by the physical senses, which means more evidence would be needed to justify executions.

How kind!

Spectral evidence was the accusation that an evil spirit or specter was being sent out from the bodies of the accused to cause torment in purported victims, leading to mental breakdowns, hysterical fits11, shrieking, bodily contortions, and other afflictions. The use of the mere accusation of specters/spirits as evidence in convictions of witchcraft was essentially a conviction by a form of evidence by assertion rather than by forms of objective, provable, empirical evidence. And though Mather and others advised the court against death, he still argued that harsh punishments were still warranted on the sole basis of spectral evidence.

This was a commonly held position at the time. Nonetheless, the spared lives of the accused were utterly ruined by the admission of spectral evidence in the legal proceedings. People lost their land, their livelihoods, their freedom (more than a year in prison), and their reputations. And more poignantly, the victims and those who witnessed their victimization lost their sense of safety, trust, faith, and community in an increasingly harsh world of social and mortal danger.

Modern Parallels—Microaggressions and Bigotry

It is likely that others have already noted the obvious parallels between the way Spectral Evidence Theory played out in the lives of the accusers and the accused during the Salem Witchcraft Trials of the 1690’s and the way Microaggression Theory currently plays out in the lives of the accusers and the accused during the Racecraft12 and Gendercraft Trials of the 2020’s—an ongoing cycle that can be fairly conceptualized as a perpetual trial, where there is a default presumption that racism, sexism, transphobia, Islamophobia, antisemitism, and/or other forms of bigotry are operational in all circumstances. In the minds of those who believe in this way, bigotry is conceived to be not only actively present in conflicts, relationships, power arrangements, hierarchies, organizations, families, opportunity gaps, conversations, and disparities but as foundational and always present.

The bigotry that is presumed to be foundational to all circumstances and scenarios more than most other forms of bigotry (especially since the summer of 2020) is the bigotry of racism.

According to Whiteness Studies scholar Robin D’Angelo, the author of Nice Racism, and White Fragility, racism should never be considered as an isolated event that happens sometimes or that happens even much of the time, but as a permanent state of affairs that underlies all things human at all times. In the handout on her website, D’Angelo states this plainly:

“The question is not ‘did racism take place’? but rather ‘how did racism manifest in that situation?’”

On the scale of human relationships on the societal level, the default assumption, according to those who see the world in this way, is that race is foundational to the existence of all disparities in outcomes. This is called structural racism or systemic or institutional racism. On the scale of laws, policies, and rules on the Federal, state, city, community, and organizational levels, the questions around the presence or foundational cause of racism concern the structures of how the resources of wealth, power, status, and influence are distributed (structural racism) and how widespread and deeply distributed those structures are (systemic or institutional racism).

On the smaller scales of human relationships and small interactions, the default assumption, according to those who see the world in this way, is that race is foundational in all interactions between people of color and white people—especially those that are perceived to be unpleasant, unfair, insulting, cruel, offensive or simply not to the liking of the person of color. These moments of perceived invalidation or disparagement are called microaggressions, a word that was coined by Harvard University psychiatrist Chester M. Pierce in 1970, referring (in its original meaning) to the insults and personal slights that non-Black Americans inflicted on Black Americans.

Over time, the word and concepts became more widely applied in American society, especially after the term was popularized by Psychologist Derald Wing Sue, who defined microaggressions broadly as occurring between people of different races, cultures, beliefs, sexual orientations, mental and physical abilities, and gender identities (and all other groups deemed marginalized), showing up in written and verbal communications and during momentary interactions between friends, foes, family, co-workers, and strangers.

The introduction of microaggressions theory and other ideological concepts and practices similarly related to the rooting out of all signs of devaluation, personal slights, biases, and bigotries has had an enormous impact on the relationships between co-workers in organizations and between people in classrooms, non-profit organizations, activist spaces, and communities large and small, often creating an atmosphere of hypervigilance and accusation13. In some cases, this theory has upended the lives of people who were unjustly accused of bigotry or whose small inadvertent infractions were blown up into something much larger and more nefarious than it actually was.

One of the most well-known examples of this atmosphere is the unfair depiction of 16-year-old Nick Sandmann and his schoolmates as harassing a Native American elder, Nathan Phillips in the winter of 2019. Virtually all of the mainstream media outlets and many celebrities added fuel to the fire with speculation, accusations, and smears, with some celebrities and even college professors casually implying that he deserved physical violence. But, it turns out that the harassment never happened, and that Phillips actively lied. Even after the full video circulated across the internet that presented an accurate picture of the events of that day, the media and the public doubled down (though some apologized publicly). Sandmann eventually won a defamation lawsuit against the Washington Post and other outlets, but the damage to his reputation was done.

Whether we believe that what happened to Nick Sandmann was the result of his belonging to a currently disfavored identity group in the eyes of the media or that the general culture has veered too far in the direction of overcorrecting and overreacting in situations involving potential discrimination, it’s important to do what we can to put the brakes on this type of atmosphere so that we can get back to doing the real work of building a society that is fair for all.

But we also want to make sure we are not going down the road of diminishing people’s real concerns about racism and other forms of bigotry.

Acknowledging and Addressing Bigotry

Structural and Systemic Bigotry

In spite of our reservations about what used to be called “callout culture” and is now called “cancel culture”, we still need to remain committed to intervening when words, actions, behaviors, systems, and policies actively deny people’s rights, threaten their sense of safety, interfere with their livelihoods, or dehumanize them.

Bigotry, unfortunately, is a naturally built-in human trait, which requires societies to put guardrails in place to prevent and address bigotry in all its forms and on all its scales.

While we can acknowledge the parallels between the hypervigilance and mania around witchcraft in the 1690’s and the hypervigilance and mania around bigotry in the 2020’s, it is also important to point out that they are not the same thing for the simple reason that the two scenarios do not share the same empirical reality.

Most people will agree that whether or not witchcraft or the Devil are real continues to be a subject of debate (and likely always will be) whereas the question of whether bigotry or hatred exist is not at all a matter of debate. Virtually nobody believes that bigotry isn’t real or that it’s still not a problem in modern society, and most will agree that bigotry and disparaging treatment can exist on any scale of individual and collective human interactions, which means that terms like structural racism, systemic racial bias, and microaggressions can sometimes be useful when applied episodically to specific situations and scenarios where there is clear evidence of disparities and injustice.

We have to be honest and vigilant about the fact that bigotry exists and that it is something we should always be on the lookout for. And for those of us who have chosen to be more public about our repudiation of the over-application of the beliefs and practices of totalizing ideologies such as Critical Social Justice (CSJ) theory, it is important to acknowledge on a consistent basis that bigotry is real and that it has harmed a great many people throughout all of human history and in our contemporary society14.

Racial Bigotry: Past and Present

One recent example of the bigotry that continues to be present in society was documented by conservative columnist, David French in a June 2024 New York Times piece. In this piece, French shares details about the overt and covert racism and ostracization that he and his family witnessed and experienced in their church, leading them to ultimately leave the church for a new place of worship after putting up with the close-mindedness and hatred that had gone on for far too long.

In it, he writes:

“The racism was grotesque. One church member asked my wife why we couldn’t adopt from Norway rather than Ethiopia. A teacher at the school asked my son if we had purchased his sister for a ‘loaf of bread.’ We later learned that there were coaches and teachers who used racial slurs to describe the few Black students at the school. There were terrible incidents of peer racism, including a student telling my daughter that slavery was good for Black people because it taught them how to live in America. Another told her that she couldn’t come to our house to play because ‘my dad said Black people are dangerous.’”

French also describes how he was encouraged by other members of his congregation to “control” his wife more and to silence her criticisms of Trump and sexism and how fellow church-goers regularly made reference to Christian Nationalists and extremist influencers such as a far-right pastor and “slavery apologist” named Douglas Wilson who stated that abolitionists were “driven by a zealous hatred of the word of God” and that “slavery produced in the South a genuine affection between the races that we believe we can say has never existed in any nation before the war or since.”

As French’s experience and the the experience of many others across the country can attest to, racism is alive and well in our current age. And when we consider the terrifying reality that has been faced by people from marginalized groups through the centuries and the lingering effects of that reality for some communities, we need to be respectful of this ongoing reality in our advocacy for a more clear-headed approach to addressing bigotry.

Along similar lines of respecting this ongoing reality, the authors of the June 2024 Pew Research report on the growing fears of many Black Americans used the phrase “racial conspiracy theories” to describe the world views of some subjects, and later chose to amend some of the language in the report. Though the report stuck to its original findings that some beliefs in the Black community about the scale of racism and beliefs regarding the intentions of the government (e.g. creating prisons with the sole intention of imprisoning Black people), the authors heeded the public outcry due to the all-too-real historical horrors perpetrated against African Americans in the legal system, medical fields, criminal justice, education, and other systems and societal norms.

One need only look at the CDC page on the USPHS Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee (more commonly known as the Tuskegee Experiment) to see how grotesque these violations have gone.

NOTE: This video is graphic, but it’s important to take an unflinching glimpse at stories like this one. Though less known than the story of Emmitt Louis Till, another African American teenaged boy who was abducted, tortured, and lynched in 1955, a 14-year-old Black boy named George Junius Stinney Jr. was unjustly accused of murdering two young white girls and was brutally executed after his conviction (which took the jury all of ten minutes). In 2014, after the case was re-opened and re-examined, the case was overturned on the basis that Stinney did not receive due process.

I want to emphasize here that racism and sexism (and all other isms and phobias) are real. To be sure, other areas of bigotry are every bit as real, too, such as homophobia, transphobia, Islamophobia, ableism, sizeism, ageism, xenophobia, colorism15, and others.

It has been to the tremendous advantage of western civilization that society has become more aware of these forms of bigotry and that countries have taken many steps over time to build a more just society that acknowledges and protects the rights of all, including those who seem different from us, and we have progressive movements to thank in large part for that. It is perhaps from the recognition of the rights of all people and the need for compassionate, empathic acceptance of difference that the progressive phrase “diversity is our strength” has gained such popularity in recent years.

But, there is an uglier, more dangerous, and sometimes violent side to the movement that has brought us this phrase and championed its principles, and that, too, needs to be acknowledged.

Intersectionality: The Problem with Overzealous Ideologies

Throughout history, the over-zealous search for evil and the all-too-human need for moral certainty and predictability in an unpredictable world have combined to lead humans to design movements and systems of thought that offer clear and unambiguous explanations and directives for building a better world. And, all too often, this search has led to an atmosphere of incessant heresy-hunting and hypervigilance in activist cultures and in the general populace as well as aggressive actions—especially on social media—against people, groups, and beliefs that have been designated as enemies of that better world.

In frameworks designed to offer explanations and guidance that are in accordance with the beliefs and values of Critical Social Justice (CSJ) theories, we see these patterns play out in a way that entrenches us in a strong sense of separation and differentness, leading to heightened feelings of of suspicion, mistrust, and anger between ourselves and others who have been categorized into permanently separate identity groups, whether those identity groups are related to gender, ethnicity, perceived political affiliation, or any other category.

One manifestation of this pattern of excessive categorization is the overuse of stigmatizing labels that are often lobbed at innocent people regardless of whether those labels are accurate. In many cases, these labels are strategically employed to silence dissent, embarrass people we disagree with, and even to ruin their lives. And, to be candid, in many cases these labels are lobbed like grenades in place of presenting an argument with objective facts, reasoning, and credible evidence as a defense mechanism because of a lack of knowledge on the part of the person lobbing the grenades.

We also see the deepening of a pattern of hypervigilance and a doubling down on a kind of selective empathy that is cultivated towards groups deemed marginalized or oppressed while expressions of outward contempt are encouraged towards people who belong to groups that have been designated as privileged oppressors16).

To put it in a clunky academic way, we see in the CSJ ideology, an increasingly structuralized, almost mathematical approach to justice and fairness, as individuals are forced into rigid categories of membership in highly structured/carved-out identity groups—in a way that betrays the reality that all individuals are unique and multi-dimensional. We see, in CSJ, rigid categorization schemes that operate from a severely reductive, mechanistic quantification of the essence of human nature and experience—the loveless structuralization of the ideals of empathy and caring rather than the organic actions of empathy and caring for people who come from all walks of life.

To put it in a simpler way, we see an ideology that teaches us that going to war against one another offers excitement and purpose and the reward of knowing that we are the righteous ones.

Jonathan Haidt captures this perfectly in an article called the Age of Outrage, which was based on a 2017 talk he gave about the ideology’s impact on universities. In this excerpt, he specifically mentions intersectionality, which is a framework developed by Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw mapping the different group identities we each belong to, how they intersect with one another, and the degree to which each identity is either oppressed or the oppressor, privileged, or marginalized.

"But what happens when young people study intersectionality? In some majors, it’s woven into many courses. Students memorize diagrams showing matrices of privilege and oppression. It’s not just white privilege causing black oppression, and male privilege causing female oppression; its heterosexual vs. LGBTQ, able-bodied vs. disabled; young vs. old, attractive vs. unattractive, even fertile vs. infertile. Anything that a group has that is good or valued is seen as a kind of privilege, which causes a kind of oppression in those who don’t have it. A funny thing happens when you take young human beings, whose minds evolved for tribal warfare and us/them thinking, and you fill those minds full of binary dimensions. You tell them that one side of each binary is good and the other is bad. You turn on their ancient tribal circuits, preparing them for battle. Many students find it thrilling; it floods them with a sense of meaning and purpose."

It helps to keep in mind that none of these behaviors and outcomes are seen as problematic by those who have chosen to follow this ideology and its practices and world views. For those who see the world in this way, the practices of separating, categorizing, stereotyping, labeling, and hyperbolizing towards the building of what they conceive to be a better world makes perfect sense.

The chief reason why these ideas and practices make perfect sense and why it feels perfectly right and natural to split society apart in service of this specific vision of social justice is the belief that there is a pervasive malevolent force that controls all of social reality17. And when a single force of malevolence is presumed to be the underlying causal agent in all scenarios, then it becomes easier to justify any and all behaviors—whether physically or socially violent—towards any individual or group that is perceived to be a part of the malevolent force or as benefitting from the malevolent force.

And as we have seen, the belief in a permanently present force of malevolence is foundational to Critical Social Justice.

The Basic Outlook of Critical Social Justice

Fear of an all powerful enemy is not unique to CSJ theories. Many of the most rigid frameworks or ideologies, both secular and religious, revolve around the presence of an all powerful enemy. For Christians, it is the Devil, and especially during the earlier centuries, heretics. For Muslims who hold to the faith in a doctrinaire way, it is the “infidel”, the non-Muslim who is not a believer in the teachings of Islam. For some who have ultra-nationalist leanings and who hold the belief that mass immigration is the intentional design of a cabal of power-brokers behind the scenes, the enemy is the Jewish population. For various communist movements, the enemy has traditionally been the bourgeoisie, the upper middle class and upper class parasites who have propped up and benefitted from capitalist systems throughout the world, and in some communist movements, the enemy is a country, especially the United States.

For adherents of Critical Social Justice ideology (CSJ), the enemy is an all-pervasive invisible force that controls the way people see the world, the way they speak about things, and what they accept as true about reality. According to CSJ theories, this reality is accepted through a kind of collective conditioning that nobody can see without the expert guidance of the almost priest-like CSJ theory-scholar. It is a reality with power-seeking as its foundation, a reality that has been set up to oppress the marginalized for the benefit of those in power.

Depending on which sector of society is being analyzed by the CSJ adherent (which is called “structural analysis”), this all-pervasive force could be the patriarchy, an almost metaphysical, all-powerful invisible force that reinforces male domination. It could be cisheteronormativity, an all-powerful invisible force that reinforces the traditional gender and sexual norms of heterosexual males and females. And it could even be fatphobia, the belief that the powers that be are intentionally propping up “thin privilege” as a beauty standard to create divisions between people of different body types, thus conquering the population in the service of protecting the power and privilege of the cisheteronormative white male patriarchy.

In the excerpt below from the book, The Counterweight Handbook: Principled Strategies for Surviving and Defeating Critical Social Justice Ideology - at Work, in Schools and Beyond, Helen Pluckrose describes the way Critical Social Justice ideology analyzes reality:

“The core tenets of Critical Social Justice are easily recognisable and distinguishable from other ethical frameworks. They rest on a belief in largely invisible systems of identity-based power into which everybody has been socialised. This simplistic belief rejects both the complexity of social reality and the individual’s agency to accept or reject bigoted ideas. This makes it different from most other ethical frameworks that oppose prejudice and discrimination.

Critical Social Justice theorists and activists apply their ‘critical’ methods to analyse systems, language and interactions in society to ‘uncover’ these power systems and make them visible to the rest of us. In their framework, these identity-based power systems include ‘Whiteness’, ‘patriarchy’, ‘colonialism’, ‘heteronormativity’ and ‘transphobia’. They are believed to infect all aspects of society and even the most benign everyday interactions. The belief that people are unable to avoid being racist, sexist, or transphobic because they have absorbed bigoted discourses from wider society is a tenet of faith that originated in postmodern thought, particularly that of Michel Foucault.

Following on from its focus on invisible systems of oppressive power and how language often serves those systems, Critical Social Justice demands enforcement of the right ways of thinking and punishment of the wrong ways of thinking.”

The term Critical Social Justice comes from the combination of the phrase social justice and the word critical as it was used by an umbrella school of thought called Critical Theory. This term was justified by education professors Özlem Sensoy and Robin DiAngelo in their book “Is Everyone Really Equal?”, and they explain in the book that their use of this term was intentional as a way to separate their approach to social justice from the mainstream view of social justice that most people have.

In their words:

‘A critical approach to social justice refers to specific theoretical perspectives that recognise that society is stratified (ie, divided and unequal) in significant and far-reaching ways along social-group lines that include race, class, gender, sexuality and ability. Critical Social Justice recognises inequality as deeply embedded in the fabric of society (ie, as structural), and actively seeks to change this.’

As I laid out in a 2021 post called “What’s Missing in the Pop CRT Debate”, I myself am partly influenced by critical theories, and specifically by Critical Pedagogy, which is the education “branch” of Critical Race Theory. One way I am influenced by critical theories is the selection for my reading and writing courses of reading and viewing materials that reflect my students’ overall demographic makeup and lived experiences as well as the demographic makeup of people from other groups. I am also influenced by the idea that there are differences of advantage between groups that we should take into consideration when crafting policies, creating curriculum, and running institutions.

Where I Agree with Critical Social Justice

I have covered these influences elsewhere, including in a 2022 post called “Shaping a Workplace Culture: the Fundamentals” which has the transcript and video of a podcast I did with the Counterweight Conference on Liberal Approaches to Diversity and Inclusion, so I won’t go into too much detail here. But I do want to outline some foundational understandings I have that are in alignment with at least the most positive spirit of Critical Social Justice theory to add balance to this piece of writing which is largely a critique of the ideology. For simplicity, here is the bullet list:

As economist Thomas Sowell pointed out in Black Rednecks and White Liberals, Europeans had a significant advantage in having access to vast arable farmland, which not only helped with sustenance, but with the leisure time to pursue technological progress, which led to inventions which also gave Europeans even more advantages.

The North American continent is isolated from other continents, which offers the advantage of protection and thus the ability to build infrastructure, manage natural resources, and pursue progress free from the destruction of war. So the idea of American Exceptionalism based purely on merit is not really supported when considering simple geographic variables.

Due to technological and other forms of progress, the English language enjoys predominance around the world. In English-speaking countries, native speakers of English have significant advantages over immigrants who speak English as a second language. In higher socioeconomic classes, the specific discourses known as Academic English or Standard American English provide easier access to money, prestige, status, and power. People who come from family and community subcultures where that is not the spoken and written discourse (for example, some African American communities where different strains of Black English are spoken) do not have that advantage as easily, which means more work needs to be put in to adapt to the Standard American English.

Black Americans and, for a long time, women, did not have the advantage of passing down home ownership and other forms of intergenerational wealth due to denial of earned benefits (for example the 1945 G.I. Bill), Jim Crow laws, the after-effects of slavery, red-lining, and other unfair treatment at the hands of their white counterparts. So there is something to the idea of cumulative structural disadvantage.

People of nonconforming gender and sexual identities have traditionally been on the margins of society, and traditionally have experienced cruelty, violence, and even death at the hands of people of traditional gender and sexual identities. In the best circumstances, lives of invisibility, secrecy, and self-suppression were the norm for generations of people. These are people who very much lived the proverbial lives of quiet desperation. Creating safe environments for their visibility and acceptance is essential.

There are, of course, many more items I could add to the list. I wanted to present the above to provide a window into my own nuanced understanding around some of the basic facts that draw people to follow frameworks like Critical Social Justice (CSJ) theories and why I cannot summarily dismiss them as completely off-base or as not genuine in their pursuit of the better world that I, too, would like to see.

The simple fact is that the world does need to be better, and this is where we can all find at least some middle ground18.

The Dark Arts of Theory Crafting

But, there are some aspects of the CSJ framework and practices that are troubling, and, considering that this ideology has become more mainstream since around 2015 and especially since 2019, it is important to recognize the most troubling patterns and to name them so that we can move beyond them and find our way back to healthy ways of solving problems. On our way to finding those healthy ways, we will need to keep in mind that one of the most powerful ways that ideologies of any stripe enjoy their dominance over the cultural, political, and moral landscape is through the use of authoritative-sounding academic language that lends an air of authority and legitimacy to ideologies and movements.

In recent years, many have had the opportunity to see how these theories are playing out in the real world, including prominent progressives who have begun to question the legitimacy and usefulness of some of the more extreme ideas and practices, including Brianna Wu, a feminist and public policy advocate who ran for office in Massachusetts and found herself on the frontlines during the 2015 Gamergate controversy during which feminists engaged (mostly white male) gamers in an ideological battle to bring in a “values-based” ethos that included the improvement of representation and treatment of women in various aspects of gaming culture.19

Hardly a newcomer to activism, the culture wars, and social theory, Wu has recently begun to voice her opposition to Critical Social Justice theories and the activist behaviors that stem from these theories. In a June 2024 Triggernometry interview called Progressive Activist Speaks Out Against Woke Madness, Wu sums up theory-crafting succinctly:

“The stuff we’re talking about on Twitter is not what they believe. So, I think there is a lot of theory-crafting in progressive spaces where they’ve got a lot of academic ideas about how elections and how power works, and I think it’s fundamentally divorced from reality.”

And this is what I mean when I use the term “disembodied theoreticalism”. It’s not that I’m saying that social theories like Critical Social Justice are not brought into practice (which traditionally, Marxists call “praxis”). I’m saying that the theories themselves are often divorced from present-day reality. They are disembodied, almost entirely abstract, and yet they hypnotize us with their totalistic claims about all of reality and with enough academic polish to appear legitimate enough to be beyond all questioning.

But, it’s not just the conclusions reached by these theories that are suspect, but also the way these conclusions are reached—the methodology that is used to reach those conclusions. As many readers likely know, the quantitative approach to research involves measuring, organizing data, and making predictions based on numbers and statistics that are themselves based on measurable, objective reality. The qualitative approach generally involves feelings and the emotional impact of phenomena.20 CSJ scholars prefer qualitative over quantitative research, which is worrying to people who are concerned about what many of the CSJ theories are suggesting21 because qualitative research often lacks verifiable results.

And sometimes, let’s be honest, the methods and conclusions can appear almost absurd when you really analyze what is being said.

Hoax Papers that Exposed Theory Crafting

Theory-crafting has had its day in the sun as an object of ridicule through a variety of hoaxes in which writers invented theories on the spot and spun them out in the form of legitimate-sounding academic papers. One of the earliest, most notable hoaxes occurred in 1996 and became known as the Sokal Affair, which involved a paper submitted to a prestigious academic journal for cultural studies called Social Text by Alan Sokal, then a Professor Emeritus of Physics at New York University22. In the paper, which was titled, “Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity", Sokal employed ludicrously complicated academic jargon and compound-complex sentences to argue that some aspects of quantum theory had inherently “progressive political implications”, which, apparently, was taken seriously enough by the journal’s editors to publish it.

Sokal later explained that the point of what he called his “little experiment” was to “demonstrate, at the very least, that some fashionable sectors of the American academic Left have been getting intellectually lazy.”

Twenty two years later, in 2018, Helen Pluckrose, James Lindsay, and Peter Boghossian published several new hoax papers that became known as the “Grievance Studies Hoax” or Sokal Squared. Two papers of note are one that deals with how dog parks contribute to rape culture and the sneakily clever revision of an excerpt from Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf that uses intersectionality and other buzz words to replace 1930’s Nazi buzzwords that ended up justifying the mistreatment of currently disfavored identity groups (in place of the word “Jews”).

I mention all this because I think it bears repeating that we should be wary of the tendency to accept completely all of the tenets of a social theory—especially simplistic theories that posit an all pervasive force of malevolence that runs through all of social reality and that is said to benefit a specific group (or groups) of people at the expense of other groups of people.

Belief in a Pervasive Malevolent Force

Pervasive Malevolent Force Theory

Once a social theory has been accepted by people who are accustomed to reading the style of academic discourse social theories are often presented in, the theory has to be translated for the general public to make it easy to understand. That’s where visual models come in.

In 2018, I thought I’d give social theory a try. As I am not trained or credentialed in psychology or social psychology, the framework I created is best regarded as a thought experiment or, at best, as an amateur social theory. If it were to be taken on as a serious a legitimate social theory, there would need to be additional research, a peer reviewed publication of that research and an effort to recruit others into the project who have the credentials and expertise in this area.

Still, I like the framework, and I think it might be useful to people, so I’m sharing it.

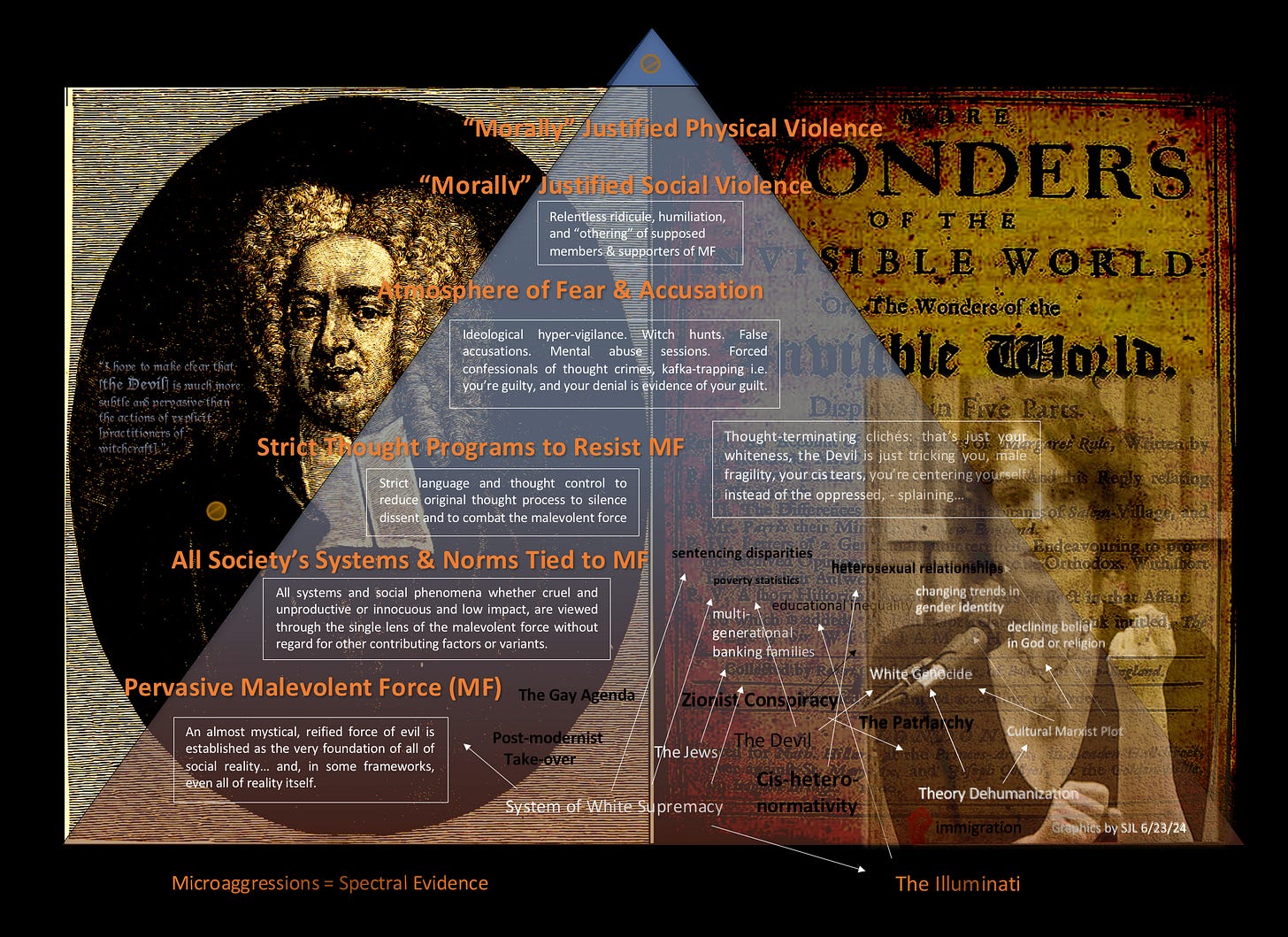

In the summer of that year, I came up with the phrase “Pervasive Malevolent Force Theory” (or simply Malevolent Force Theory) and created a visual model of the theory based in part on some patterns of behavior I had been noticing on social media, in educational institutions, and in activist spaces I had been a part of. Drawing upon the work of Robert Jay Lifton, Eric Hoffer, and others on the problem of ideological totalism and what I knew about psychological trauma responses, especially hypervigilance, I designed this framework with the hope that it might be useful to others in understanding what was happening all around them—everywhere, like, ironically… a pervasive malevolent force. 😉

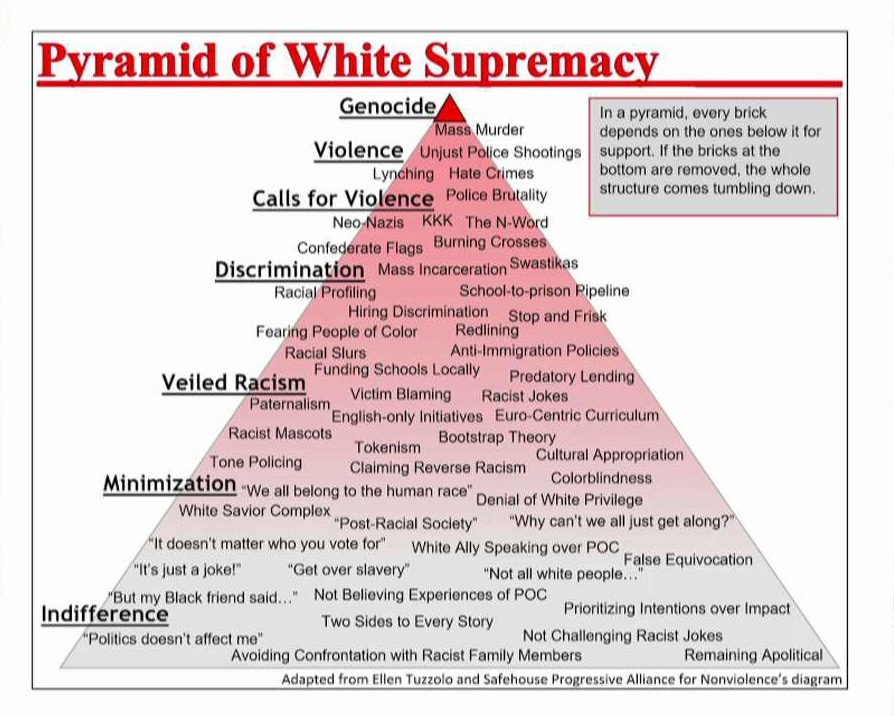

During the 2016 Presidential election year and Brexit vote, oppression pyramid models depicting patterns of marginalization from innocuous putdowns all the way up to genocide began to become more widely circulated throughout social media platforms. These pyramid models continue to be popular in a variety of places, representing various forms of oppression from rape culture and patriarchy, to capitalism, homophobia, sexism, and other forms of oppression.

The most popular pyramid is the Pyramid of White Supremacy, which offers a visual representation of some of the principal axioms in Critical Race Theory, namely that all white people are racist and that all of society’s norms, laws, policies, and discourses are structured by, infused with, made up of, and founded upon White Supremacy. This pyramid has become popular and enjoys wide acceptance, having been presented to high school and college classrooms, meditation centers, popular television shows, online magazines, teacher’s associations, activist spaces, religious organizations, and even counseling centers across the United States and other English-speaking countries, helping to further cement an already hypervigilant atmosphere in which racism, White Supremacy, and fascism is believed by many to be seemingly everywhere.

As this pyramid and other pyramid models convey, racism is not just a behavior or set of beliefs that can be discovered, exposed, and defeated. Instead, we are instructed to believe that racism is the way things are at all times and in all places, and that White Supremacy (and its behaviors known collectively as “White Supremacy Culture”) is the default attitude that structures and guides the minds and hearts of all people in the majority of the population (which continues to be majority white as of 2024).

In some cases, the presence of White Supremacy takes on a whole other level in the CSJ perspective, appearing as a kind of mystical ever-present force that cannot be named or proven to exist but that we know intuitively is always there to haunt, to control, and to terrorize23.

This perspective has become so popular in recent years that even a mainstream television medical drama called “New Amsterdam” included it in a 2019 episode called “Sabbath”, in which the benign tumor of a 13 year old boy named Cephas was diagnosed by the doctor to have its root cause in the pain of living in a world structured by racism. Because there was no code for racism to type into the computer system, the doctor had to find a way to prove the racism diagnosis to bill the insurance company, so he turned to the research on trauma and stress.

This metaphysical leap in racial theorizing echoes what Ibram X. Kendi spoke about in a Manhattan church in the same year this episode was aired, when Kendi took the physical danger of racism to another level, stating that “more white people are finally beginning to realize how White Supremacy and how even Whiteness itself is killing them”, implying that this almost gaseous substance called Whiteness was a kind of disease that was deadly if contracted, not only to people assigned the group identity of “white” but to the whole world.

Kendi sums it up for us:

Whiteness is “posing an existential threat to humanity.”

With a perspective like this one, we can see that the belief in a Pervasive Malevolent Force (in this case, Whiteness) can escalate to the belief that the ways in which this malevolent force is able to operate in our lives truly has no limits.

The Reality of Racial Trauma (and other forms of trauma)

As I am nearing the end of this writing, I want to pause for a moment to emphasize that we should not underestimate the traumatizing impact of prolonged psychological stress.

Multiple studies over the years suggest a direct link between spikes in the stress hormone cortisol during prolonged periods of high stress and various health issues such as the suppression of the immune system, weight gain, depression, anxiety, and susceptibility to infections. Numerous studies also link the trauma of prolonged psychological stress to the development and/or enlargement of cancerous tumors, so the causes and symptoms of trauma cannot be easily dismissed as “woke nonsense.”24

For some people who belong to minoritized25 communities, there can be adverse health consequences resulting from the prolonged stress of being in environments that are less accepting of people in the minority. According to some studies on complex racial trauma, there can also be adverse effects for individual minorities who acutely feel a sense of “otherness”, the deeply felt sense that one stands out as somebody who is not part of the “normal”.

These individuals are often made to feel like irrelevant satellites orbiting around the margins of the default "planet" (or mainstream normalcy) of the majority. While historically, health consequences are much worse for those who live and work in communities that openly dismiss, revile, and attack them, the experience of feeling invisible or as feeling like one is just a bit player in another group’s story can cause prolonged stress, leading to depression, alienation, resentment, and internalized self-devaluation26.

In all likelihood, there will always be disagreements among scholars and laypersons regarding the scope, scale, and intensity of the trauma experienced by some who belong to minoritized identity groups27. But, it’s important that we never stop recognizing the reality of trauma itself; it is widespread enough to merit our respect.

But while we need to respect the reality of trauma, we encounter serious problems when we reduce every situation to trauma (e.g., racial trauma, gender trauma, childhood trauma). By rejecting the approach of multi-variant analysis in diagnosing situations, medical or otherwise, we miss the opportunity to find the true cause or causes of a situation because we have already locked ourselves in to a preconceived idea.

And in the process, we also run the risk of engraving a paranoid mindset into our minds, seeing threat everywhere, including places where there is no objective threat.

Over-diagnosis of Threat and Trauma

It would be unrealistic to list all possible factors contributing to situations, but a few include racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, weather conditions, availability of weapons, developmental capacities, psychological types, presence of neurosis, genetic diseases, sexual desirability, envy, exhaustion, Lyme disease, food chemicals, pesticides, language barriers, social customs, economic conditions, and more.

Life is more complex than some theories would have us believe, and when we deny the existence of other variables and choose to perseverate on a single cause to which we have assigned malicious intentions and unchecked power, we can become paralyzed with fear and rage, an unhealthy combination that can lead to overactive thoughts and reactive—and potentially escalated—behaviors designed to get rid of the single cause.28

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt and legal scholar Greg Lukianoff cover the unhealthy mindset that ignores the complexities of reality in their groundbreaking book, “The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure,” offering important insights into the outcomes of the unhealthy behavioral pattern of constantly probing the environment for evidence that one is being attacked or devalued, a symptom known as hypervigilance, one of the main symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Hypervigilance involves the repetition of fearful or suspicious thoughts in our heads, a kind of script that races through our minds in an endless loop, telling us that we are in danger and whispering to us in a conspiratorial tone that we must stay alert for signs of danger and to expect this danger to be present during every moment, even though it may be hidden.

The Coddling of the American Mind also highlights ways to off set this mindset, including the widely applied therapeutic practice of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), which is a technique that teaches us how to reframe the negative stories and beliefs we are telling ourselves. In some ways, it can be said that CBT is a technique that is the mirror opposite of the approach to sense-making and adaptation to situations that is favored by those adhering to microaggressions theory. Put simply, CBT is the antidote to the poison causing paranoia. Searching for microaggressions is the poison.

Over-diagnosing the presence, prevalence, and power of a Pervasive Malevolent Force fosters an us-against-them mindset, leading to the constant scanning of environments for signs that we are being attacked or diminished by a hidden source. Eventually, this mindset trains individuals to see malevolence everywhere, from off-putting jokes to unreturned phone calls. This perception can also lead to viewing social movements and their followers we perceive to be on the wrong side as one-dimensional and malevolent, triggering fight, flight, or freeze responses, and causing physical and mental ailments due to the self-produced rise in excessive cortisol.

Another factor exacerbating the pendulous swing between the warlike mindset and the fearful, paralyzed mindset is the 24-hour news cycle and incessant internet noise that leaves many exhausted, tuned out, or lost in entertainment and addiction.29 Though I’m not a psychologist or sociologist, I see these trauma responses as stemming not so much from the omnipresence of a Pervasive Malevolent Force, but in our collective tendency to be on the constant search for one.

The Role of Ideology in Scaring Us

In the New Amsterdam episode mentioned above, Cephas, the 13-year-boy with the stomach tumor eventually surrendered to this mindset after a series of leading questions from his doctors suggesting that he was the victim of bigotry and disrespect at every turn. This victimization story was superimposed over the simple act of a librarian not allowing the boy to take out a book that had been reserved for students in the Gifted and Talented program.

Instead of viewing this situation as an example of following the rules, Cephas was encouraged by his doctors to view the librarian’s action as representing the librarian’s belief that the boy could not possibly have been gifted because he was Black. Cephas initially denied having any stress, but after being informed by the diagnosing doctor about cortisol, PTSD, stress, and anxiety, and after submitting to persistent leading questions about feeling threatened or harassed, the boy became convinced of the doctor's diagnosis that his tumor was indeed caused by racism.

It’s clear from the jargon and from the leading questions that the doctor was coming from confirmation bias informed by the chief underlying claim of CSJ theory—that the whole world is structured by White Supremacy. It becomes obvious even to the casual viewer that the doctor's questions presupposing the omnipresence of racism are based on ideology. It becomes especially clear when we hear that the cause of Cephas’s excessive cortisol levels was the boy’s "social resistance" to the "dominant culture", two buzzwords clearly drawn from CSJ theory30.

When a person of authority uses suggestive questioning like this and feeds suspicious thinking patterns into the mind of an adolescent, we run into trouble. We see this pattern played out in the political sphere where elected leaders rev up the masses with these thoughts and in the educational sphere where entire curricula are designed with the Pervasive Malevolent Force mindset.

Although the example I have chosen to highlight is just a single episode of a medical drama, in which a boy is diagnosed as having what the doctor called “internalization of stress due to his inability to name what he was feeling”, this fictional story mirrors the way such a diagnosis is crassly applied across all areas of society, including one of the most well-known instances in which racism was declared a national health crisis,31 during the summer of 2020, justifying the relaxation of Covid-19 social distancing rules during the George Floyd protests.

This television episode is not an isolated incident. Not by a long shot.

Clearly, a case can be made that ideology plays a large role in the perception that we are in harm’s way even in cases where there is no real evidence for it. This is especially the case in ideologies that come from the larger umbrella of Critical Social Justice (CSJ), and that is why more of us need to be standing up to this ideology’s incursion into our society’s policies, norms, laws, and institutions.

A Life of Fear

Critical Social Justice (CSJ) worldviews tie all disparities, misunderstandings, and opportunity gaps between groups labeled as oppressors and the oppressed to a single variable, disregarding factors like economics, geography, personality types, and individual skills. Aligning with the most basic tenet of CSJ theory, every word, deed, and behavior is linked to a single underlying foundation that must be named and opposed at all times.

Viewing these frameworks as highlighting the escalation from minor slights to serious crimes up to and including violence, rape, and even genocide can be helpful.32

But viewing all of human reality as structured by White Supremacy, rape culture, and hatred of gay and trans people and other groups, can lead to collective paranoia. Such a perspective about reality can lead to an environment where people are on constant alert, ever-ready to make accusations and to search for and root out all beliefs, words, and behaviors considered to be supportive of or as actively representing the pervasive malevolent force.

It is a life of fear.

Conclusion: Embracing Epistemic Humility

In OK, Groomer and the Dangers of Crying Wolf, a Queer Majority piece by Jamie Paul, we are reminded of the increased danger of polarization and societal stalemate when the loudest, most extreme, and most radical voices dominate the conversation.

On the conservative side, these voices are the “OK Groomer” accusers who tie every ounce of LGBTQ+ advocacy to the sexual exploitation and indoctrination of minors, conflating radical leftist educators and queer kids on TikTok with the efforts of moderately progressive educators to promote safety and acceptance for gender nonconforming people and sexual minorities. On the liberal side (the more extreme illiberal progressive wing), these voices are the “everyone is a racist, fascist, white supremacist transphobe” accusers who tolerate no dissent or questioning of their rigid dogmas, punishing any free thought with reputation smears, content to ruin lives for the cause.

It’s not easy to resist joining the illiberal wing of our own side (whether liberal or conservative), but, as Jamie Paul puts it, no matter how outrageous our opponents may seem to us or how welcoming the illiberal wing of any side seems to us, “siding with one illiberal ideology [on any side] to oppose another is never wise.”

He’s right.

If we hope for a fairer society and a cooling down of the culture war, we need to recognize our own side’s tendencies—and our own tendencies as individuals—towards fear and illiberalism.

For those who follow Critical Social Justice (CSJ) and some of the right-leaning ideologies that have an all-encompassing enemy as a central component; fear and illiberalism manifest as the belief in a pervasive, malevolent force that is adversarial to all that is good, operating across race, gender, race, creed, ethnicity, and other lines of human life. As this belief becomes more central to the political and psychological existence of CSJ followers and followers of hard right-leaning ideologies, it can begin to seem like an almost metaphysical reality that underlies all things33, which can be quite a scary thing to believe in.

And the more detached these beliefs become from actual reality, the more justifiable it becomes to embrace extreme actions and policies in service of the theory. Whether it’s the belief that witchcraft has overtaken a colonial village in 17th century America, the concern that most LGBTQ+ people are really after our children, or the belief that crypto-fascism is the secret force that runs through all of society’s laws and norms, it makes sense to believe that only proper response to such threats is to lay waste to our opponents in a way that is total and complete.